Dr Julie Seibt

Academic and research departments

Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, Discipline: Clinical Sciences, Surrey Sleep Research Centre.About

Biography

After graduating in Cognitive Neuroscience from Aix-Marseille Provence University, I obtained an MS in Neuroscience (2001) and a PhD in Developmental Neurobiology in 2005 from the University Claude Bernard in Lyon. For my postdoctoral work, I turned to my long-term passion which is to understand how sleep helps brain functions. In 2006, I took a post-doctoral position in the laboratory of Marcos Frank at the University of Pennsylvania (USA) where I started to explore the link between sleep and brain plasticity during development. My research there focused on the role of mRNA translation as mechanism for brain plasticity consolidation during sleep. In 2010, I joined the group of Matthew Larkum at the Charité-Universtätsmedizin Berlin where I developed an in vivo calcium imaging technique to investigate the influence of sleep and sleep oscillations on activity in neuronal dendrites during natural sleep in rodents. This led to the discovery that calcium activity in cortical dendrites is linked to spindles, a sleep oscillation important for cognitive function in humans and animals. I joined the University of Surrey in 2016 and since 2021, I am a Senior Lecturer in Sleep & Plasticity at the Surrey Sleep Research Centre (SSRC), Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences.

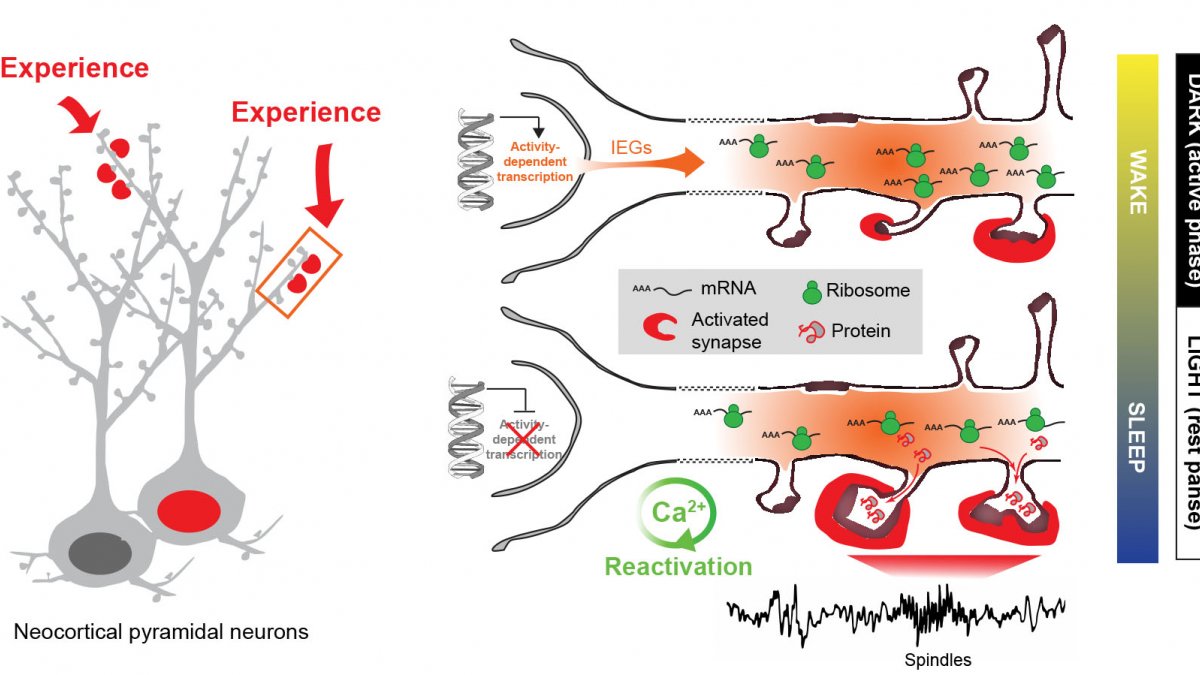

My current research focuses on investigating the link between the various aspects of sleep dynamics (e.g. sleep stages and oscillations) and mechanisms of synaptic plasticity. In particular, my work focuses on the influence of sleep and experience on molecular and cellular changes in synapses and dendrites in the cortex.

Areas of specialism

University roles and responsibilities

- Module coordinator for BMS3064 - Neuroscience, from molecules to Mind

- Chair of the User group

- Member of Animal Welfare and Ethical Review Body

My qualifications

Affiliations and memberships

Experience-dependent gene expression across sleep and wakefulness - Model (adapted from Seibt & Frank, Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2019)

Julie Seibt

Julie SeibtResearchResearch interests

Every day our brain disconnects from the environment during sleep and interfering with this process has detrimental effects on the development and maintenance of our cognitive functions. What is so special about the sleeping brain that helps our brain to grow and learn?

During sleep our brain is far from resting and enters a highly organised pattern of global changes in activity, cycling through periods of large scale network synchronization (i.e. NREM sleep) and desynchronized activity (i.e. REM sleep). Both sleep stages are important for maintaining proper cognition but the underlying physiology is not well understood.

My main research interest is to understand the link between sleep stages and synaptic plasticity - the fundamental mechanism that allows us to adapt and change communication between neurons in response to experience. We take a multidisciplinary experimental approach, including electrophysiology, molecular, in vivo optical imaging methods and behavioural manipulations in the rodent model.

Projects that we currently pursue include:

- The influence of sleep and experience on molecular changes at synapses (omics approaches)

- The influence of sleep and experience on in vivo calcium activity in cortical dendrites

- The physiology and role of sleep spindles

Sleep is a great unknown and I am thus open to any new ideas, projects and collaborations...

Research collaborations

Dr Àlex Bayés - Sant Pau Biomedical Research Institute, Spain

Dr Mark Collin - University of Sheffield, UK

Prof André Gerber - University of Surrey, UK

Prof Matthew Larkum - Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Germany

Dr Jini Naidoo - University of Pennsylvania, USA

Research interests

Every day our brain disconnects from the environment during sleep and interfering with this process has detrimental effects on the development and maintenance of our cognitive functions. What is so special about the sleeping brain that helps our brain to grow and learn?

During sleep our brain is far from resting and enters a highly organised pattern of global changes in activity, cycling through periods of large scale network synchronization (i.e. NREM sleep) and desynchronized activity (i.e. REM sleep). Both sleep stages are important for maintaining proper cognition but the underlying physiology is not well understood.

My main research interest is to understand the link between sleep stages and synaptic plasticity - the fundamental mechanism that allows us to adapt and change communication between neurons in response to experience. We take a multidisciplinary experimental approach, including electrophysiology, molecular, in vivo optical imaging methods and behavioural manipulations in the rodent model.

Projects that we currently pursue include:

- The influence of sleep and experience on molecular changes at synapses (omics approaches)

- The influence of sleep and experience on in vivo calcium activity in cortical dendrites

- The physiology and role of sleep spindles

Sleep is a great unknown and I am thus open to any new ideas, projects and collaborations...

Research collaborations

Dr Àlex Bayés - Sant Pau Biomedical Research Institute, Spain

Dr Mark Collin - University of Sheffield, UK

Prof André Gerber - University of Surrey, UK

Prof Matthew Larkum - Humboldt Universität zu Berlin, Germany

Dr Jini Naidoo - University of Pennsylvania, USA

Supervision

Postgraduate research supervision

Martin Smith (postdoctoral fellow)

Farahnaz Yazdanpanah Faragheh (PhD student)

Alumni

José Lucas Santos (PhD student) - now postdoctoral fellow at Cambridge University

Danique Zantinge (Master student)

Isla Buchanan (Master student)

Claudia Carnell (Master student)

Teaching

BMS2048: Neuroscience, from Neurons to Behaviour

BMS3064: Neuroscience, from Molecules to Mind (Coordinator)

Publications

T-type voltage-dependent calcium channels may play an important role in synaptic plasticity, but lack of specific antagonists has hampered investigation into this possible function. We investigated the role of the T-type channel in a canonical model of in-vivo cortical plasticity triggered by monocular deprivation. We identified a compound (TTA-I1) with subnanomolar potency in standard voltage clamp assays and high selectivity for the T-type channel. When infused intracortically, TTA-I1 reduced cortical plasticity triggered by monocular deprivation while preserving normal visual response properties. These results show that the T-type calcium channel plays a central role in cortical plasticity. NeuroReport 20:257-262 (C) 2009 Wolters Kluwer Health vertical bar Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

How sleep influences brain plasticity is not known. In particular, why certain electroencephalographic (EEG) rhythms are linked to memory consolidation is poorly understood. Calcium activity in dendrites is known to be necessary for structural plasticity changes, but this has never been carefully examined during sleep. Here, we report that calcium activity in populations of neocortical dendrites is increased and synchronised during oscillations in the spindle range in naturally sleeping rodents. Remarkably, the same relationship is not found in cell bodies of the same neurons and throughout the cortical column. Spindles during sleep have been suggested to be important for brain development and plasticity. Our results provide evidence for a physiological link of spindles in the cortex specific to dendrites, the main site of synaptic plasticity.

Many lines of evidence indicate that important traits of neuronal phenotype, such as cell body position and neurotransmitter expression, are specified through complex interactions between extrinsic and intrinsic genetic determinants. However, the molecular mechanisms specifying neuronal connectivity are less well understood at the transcriptional level. Here we demonstrate that the bHLH transcription factor Neurogenin2 cell autonomously specifies the projection of thalamic neurons to frontal cortical areas. Unexpectedly, Ngn2 determines the projection of thalamic neurons to specific cortical domains by specifying the responsiveness of their axons to cues encountered in an intermediate target, the ventral telencephalon. Our results thus demonstrate that in parallel to their well-documented proneural function, bHLH transcription factors also contribute to the specification of neuronal connectivity in the mammalian brain

Brain plasticity is induced by learning during wakefulness and is consolidated during sleep. But the molecular mechanisms involved are poorly understood and their relation to experience-dependent changes in brain activity remains to be clarified. Localised mRNA translation is important for the structural changes at synapses supporting brain plasticity consolidation. The translation mTOR pathway, via phosphorylation of 4E-BPs, is known to be activate during sleep and contributes to brain plasticity, but whether this activation is specific to synapses is not known. We investigated this question using acute exposure of rats to an enriched environment (EE). We measured brain activity with EEGs and 4E-BP phosphorylation at cortical and cerebellar synapses with Western blot analyses. Sleep significantly increased the conversion of 4E-BPs to their hyperphosphorylated forms at synapses, especially after EE exposure. EE exposure increased oscillations in the alpha band during active exploration and in the theta-to-beta (4–30 Hz) range, as well as spindle density, during NREM sleep. Theta activity during exploration and NREM spindle frequency predicted changes in 4E-BP hyperphosphorylation at synapses. Hence, our results suggest a functional link between EEG and molecular markers of plasticity across wakefulness and sleep.

Sleep consolidates experience-dependent brain plasticity, but the precise cellular mechanisms mediating this process are unknown [1]. De novo cortical protein synthesis is one possible mechanism. In support of this hypothesis, sleep is associated with increased brain protein synthesis [2, 3] and transcription of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) involved in protein synthesis regulation [4, 5]. Protein synthesis in turn is critical for memory consolidation and persistent forms of plasticity in vitro and in vivo [6, 7]. However, it is unknown whether cortical protein synthesis in sleep serves similar functions. We investigated the role of protein synthesis in the sleep-dependent consolidation of a classic form of cortical plasticity in vivo (ocular dominance plasticity, ODP; [8, 9]) in the cat visual cortex. We show that intracortical inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent protein synthesis during sleep abolishes consolidation but has no effect on plasticity induced during wakefulness. Sleep also promotes phosphorylation of protein synthesis regulators (i.e., 4E-BP1 and eEF2) and the translation (but not transcription) of key plasticity related mRNAs (ARC and BDNF). These findings show that sleep promotes cortical mRNA translation. Interruption of this process has functional consequences, because it abolishes the consolidation of experience in the cortex.

Imprinting is an epigenetic mechanism that restrains the expression of about 100 genes to one allele depending on its parental origin. Several imprinted genes are implicated in neurodevelopmental brain disorders, such as autism, Angelman, and Prader-Willi syndromes. However, how expression of these imprinted genes is regulated during neural development is poorly understood. Here, using single and double KO animals for the transcription factors Neurogenin2 (Ngn2) and Achaetescute homolog 1 (Ascl1), we found that the expression of a specific subset of imprinted genes is controlled by these proneural genes. Using in situ hybridization and quantitative PCR, we determined that five imprinted transcripts situated at the Dlk1-Gtl2 locus (Dlk1, Gtl2, Mirg, Rian, Rtl1) are upregulated in the dorsal telencephalon of Ngn2 KO mice. This suggests that Ngn2 influences the expression of the entire Dlk1-Gtl2 locus, independently of the parental origin of the transcripts. Interestingly 14 other imprinted genes situated at other imprinted loci were not affected by the loss of Ngn2. Finally, using Ngn2/Ascl1 double KO mice, we show that the upregulation of genes at the Dlk1-Gtl2 locus in Ngn2 KO animals requires a functional copy of Ascl1. Our data suggest a complex interplay between proneural genes in the developing forebrain that control the level of expression at the imprinted Dlk1-Gtl2 locus (but not of other imprinted genes). This raises the possibility that the transcripts of this selective locus participate in the biological effects of proneural genes in the developing telencephalon.

Sleep is well known to benefit cognitive function. In particular, sleep has been shown to enhance learning and memory in both humans and animals. While the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood, it has been suggested that brain activity during sleep modulates neuronal communication through synaptic plasticity. These insights were mostly gained using electrophysiology to monitor ongoing large scale and single cell activity. While these efforts were instrumental in the characterisation of important network and cellular activity during sleep, several aspects underlying cognition are beyond the reach of this technology. Neuronal circuit activity is dynamically regulated via the precise interaction of different neuronal and non-neuronal cell types and relies on subtle modifications of individual synapses. In contrast to established electrophysiological approaches, recent advances in imaging techniques, mainly applied in rodents, provide unprecedented access to these aspects of neuronal function in vivo. In this review, we describe various techniques currently available for in vivo brain imaging, from single synapse to large scale network activity. We discuss the advantages and limitations of these approaches in the context of sleep research and describe which particular aspects related to cognition lend themselves to this kind of investigation. Finally, we review the few studies that used in vivo imaging in rodents to investigate the sleeping brain and discuss how the results have already significantly contributed to a better understanding on the complex relation between sleep and plasticity across development and adulthood.

Spindles are ubiquitous oscillations during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. A growing body of evidence points to a possible link with learning and memory, and the underlying mechanisms are now starting to be unveiled. Specifically, spindles are associated with increased dendritic activity and high intracellular calcium levels, a situation favourable to plasticity, as well as with control of spiking output by feed-forward inhibition. During spindles, thalamocortical networks become unresponsive to inputs, thus potentially preventing interference between memory-related internal information processing and extrinsic signals. At the system level, spindles are co-modulated with other major NREM oscillations, including hippocampal sharp wave-ripples (SWRs) and neocortical slow waves, both previously shown to be associated with learning and memory. The sequential occurrence of reactivation at the time of SWRs followed by neuronal plasticity-promoting spindles is a possible mechanism to explain NREM sleep-dependent consolidation of memories.

Sleep is believed to play an important role in cognitive functions. The underlying mechanisms of the relationship between the effects of waking experiences (i.e., sleep deprivation [SD] and enriched environment [EE]) on sleep characteristics (sleep states and brain waves) are believed to be beneficial. Sleep is divided into two main stages: non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) and REM sleep. Electroencephalogram (EEG) in adult mice was used in order to record and compare changes in sleep stages and specific brain waves (i.e., oscillations) during sleep following those waking experiences. Results showed that both waking experiences significantly increase NREM sleep amount and duration. However, SD and EE differentially affect slow wave activity (SWA: 0.5–4.0 Hz) and spindle-rich sigma activity (9–16 Hz), the two main sleep oscillations of NREM sleep. The conclusions were that extended wakefulness (i.e., SD) and learning (i.e., EE) differentially affect NREM EEG signatures (SWA, spindles). The obtained results support previous data which shows that these oscillations are important for cognition and further suggest that their differential regulation by experiences may account for different functions.

Insufficient sleep is a global problem with serious consequences for cognition and mental health.1 Synapses play a central role in many aspects of cognition, including the crucial function of memory consolidation during sleep.2 Interference with the normal expression or function of synapse proteins is a cause of cognitive, mood, and other behavioral problems in over 130 brain disorders.3 Sleep deprivation (SD) has also been reported to alter synapse protein composition and synapse number, although with conflicting results.4,5,6,7 In our study, we conducted synaptome mapping of excitatory synapses in 125 regions of the mouse brain and found that sleep deprivation selectively reduces synapse diversity in the cortex and in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Sleep deprivation targeted specific types and subtypes of excitatory synapses while maintaining total synapse density (synapse number/area). Synapse subtypes with longer protein lifetimes exhibited resilience to sleep deprivation, similar to observations in aging and genetic perturbations. Moreover, the altered synaptome architecture affected the responses to neural oscillations, suggesting that sleep plays a vital role in preserving cognitive function by maintaining the brain's synaptome architecture.

Study Objectives: The effects of hypnotics on sleep-dependent brain plasticity are unknown. We have shown that sleep enhances a canonical model of in vivo cortical plasticity, known as ocular dominance plasticity (ODP). We investigated the effects of 3 different classes of hypnotics on ODP. Design: Polysomnographic recordings were performed during the entire experiment (20 h). After a baseline sleep/wake recording (6 h), cats received 6 h of monocular deprivation (MD) followed by an i.p. injection of triazolam (1-10 mg/kg i.p.), zolpidem (10 mg/kg i.p.), ramelteon (0.1-1 mg/kg i.p.), or vehicle (DMSO i.p.). They were then allowed to sleep ad lib for 8 h, after which they were prepared for optical imaging of intrinsic cortical signals and single-unit electrophysiology. Setting: Basic neurophysiology laboratory Patients or Participants: Cats (male and female) in the critical period of visual development (postnatal days 28-41) Interventions: N/A Measurements and Results: Zolpidem reduced cortical plasticity by ~50% as assessed with optical imaging of intrinsic cortical signals. This was not due to abnormal sleep architecture because triazolam, which perturbed sleep architecture and sleep EEGs more profoundly than zolpidem, had no effect on plasticity. Ramelteon minimally altered sleep and had no effect on ODP. Conclusions: Our findings demonstrate that alterations in sleep architecture do not necessarily lead to impairments in sleep function. Conversely, hypnotics that produce more “physiological” sleep based on polysomnography may impair critical brain processes, depending on their pharmacology.

The regulation of mRNA translation plays an essential role in neurons, contributing to important brain functions, such as brain plasticity and memory formation. Translation is conducted by ribosomes, which at their core consist of ribosomal proteins (RPs) and ribosomal RNAs. While translation can be regulated at diverse levels through global or mRNA-specific means, recent evidence suggests that ribosomes with distinct configurations are involved in the translation of different subsets of mRNAs. However, whether and how such proclaimed ribosome heterogeneity could be connected to neuronal functions remains largely unresolved. Here, we postulate that the existence of heterologous ribosomes within neurons, especially at discrete synapses, subserve brain plasticity. This hypothesis is supported by recent studies in rodents showing that heterogeneous RP expression occurs in dendrites, the compartment of neurons where synapses are made. We further propose that sleep, which is fundamental for brain plasticity and memory formation, has a particular role in the formation of heterologous ribosomes, specialised in the translation of mRNAs specific for synaptic plasticity. This aspect of our hypothesis is supported by recent studies showing increased translation and changes in RP expression during sleep after learning. Thus, certain RPs are regulated by sleep, and could support different sleep functions, in particular brain plasticity. Future experiments investigating cell-specific heterogeneity in RPs across the sleep-wake cycle and in response to different behaviour would help address this question

Rapid eye movement sleep is maximal during early life, but its function in the developing brain is unknown. We investigated the role of rapid eye movement sleep in a canonical model of developmental plasticity in vivo (ocular dominance plasticity in the cat) induced by monocular deprivation. Preventing rapid eye movement sleep after monocular deprivation reduced ocular dominance plasticity and inhibited activation of a kinase critical for this plasticity (extracellular signal–regulated kinase). Chronic single-neuron recording in freely behaving cats further revealed that cortical activity during rapid eye movement sleep resembled activity present during monocular deprivation. This corresponded to times of maximal extracellular signal–regulated kinase activation. These findings indicate that rapid eye movement sleep promotes molecular and network adaptations that consolidate waking experience in the developing brain.

It is commonly accepted that brain plasticity occurs in wakefulness and sleep. However, how these different brain states work in concert to create long-lasting changes in brain circuitry is unclear. Considering that wakefulness and sleep are profoundly different brain states on multiple levels (e.g., cellular, molecular and network activation), it is unlikely that they operate exactly the same way. Rather it is probable that they engage different, but coordinated, mechanisms. In this article we discuss how plasticity may be divided across the sleep–wake cycle, and how synaptic changes in each brain state are linked. Our working model proposes that waking experience triggers short-lived synaptic events that are necessary for transient plastic changes and mark (i.e., ‘prime’) circuits and synapses for further processing in sleep. During sleep, synaptic protein synthesis at primed synapses leads to structural changes necessary for long-term information storage.

Sleep improves cognition and is necessary for normal brain plasticity, but the precise cellular and molecular mechanisms mediating these effects are unknown. At the molecular level, experience-dependent synaptic plasticity triggers new gene and protein expression necessary for long-lasting changes in synaptic strength.1 In particular, translation of mRNAs at remodeling synapses is emerging as an important mechanism in persistent forms of synaptic plasticity in vitro and certain forms of memory consolidation.2 We have previously shown that sleep is required for the consolidation of a canonical model of in vivo plasticity (i.e., ocular dominance plasticity [ODP] in the developing cat).3 Using this model, we recently showed that protein synthesis during sleep participates in the consolidation process. We demonstrate that activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin [mTOR] pathway, an important regulator of translation initiation,4 is necessary for sleep-dependent ODP consolidation and that sleep promotes translation (but not transcription) of proteins essential for synaptic plasticity (i.e., ARC and BDNF). Our study thus reveals a previously unknown mechanism operating during sleep that consolidates cortical plasticity in vivo.

Neocortical projection neurons, which segregate into six cortical layers according to their birthdate, have diverse morphologies, axonal projections and molecular profiles, yet they share a common cortical regional identity and glutamatergic neurotransmission phenotype. Here we demonstrate that distinct genetic programs operate at different stages of corticogenesis to specify the properties shared by all neocortical neurons. Ngn1 and Ngn2 are required to specify the cortical (regional), glutamatergic (neurotransmitter) and laminar (temporal) characters of early-born (lower-layer) neurons, while simultaneously repressing an alternative subcortical, GABAergic neuronal phenotype. Subsequently, later-born (upper-layer) cortical neurons are specified in an Ngn-independent manner, requiring instead the synergistic activities of Pax6 and Tlx, which also control a binary choice between cortical/glutamatergic and subcortical/GABAergic fates. Our study thus reveals an unanticipated heterogeneity in the genetic mechanisms specifying the identity of neocortical projection neurons.

Ocular dominance plasticity in the developing primary visual cortex is initiated by monocular deprivation (MD) and consolidated during subsequent sleep. To clarify how visual experience and sleep affect neuronal activity and plasticity, we continuously recorded extragranular visual cortex fast-spiking (FS) interneurons and putative principal (i.e., excitatory) neurons in freely behaving cats across periods of waking MD and post-MD sleep. Consistent with previous reports in mice, MD induces two related changes in FS interneurons: a response shift in favor of the closed eye and depression of firing. Spike-timing–dependent depression of open-eye–biased principal neuron inputs to FS interneurons may mediate these effects. During post-MD nonrapid eye movement sleep, principal neuron firing increases and becomes more phase-locked to slow wave and spindle oscillations. Ocular dominance (OD) shifts in favor of open-eye stimulation—evident only after post-MD sleep—are proportional to MD-induced changes in FS interneuron activity and to subsequent sleep-associated changes in principal neuron activity. OD shifts are greatest in principal neurons that fire 40–300 ms after neighboring FS interneurons during post-MD slow waves. Based on these data, we propose that MD-induced changes in FS interneurons play an instructive role in ocular dominance plasticity, causing disinhibition among open-eye–biased principal neurons, which drive plasticity throughout the visual cortex during subsequent sleep.

Sleep is thought to consolidate changes in synaptic strength, but the underlying mechanisms are unknown. We investigated the cellular events involved in this process during ocular dominance plasticity (ODP)—a canonical form of in vivo cortical plasticity triggered by monocular deprivation (MD) and consolidated by sleep via undetermined, activity-dependent mechanisms. We find that sleep consolidates ODP primarily by strengthening cortical responses to nondeprived eye stimulation. Consolidation is inhibited by reversible, intracortical antagonism of NMDA receptors (NMDARs) or cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) during post-MD sleep. Consolidation is also associated with sleep-dependent increases in the activity of remodeling neurons and in the phosphorylation of proteins required for potentiation of glutamatergic synapses. These findings demonstrate that synaptic strengthening via NMDAR and PKA activity is a key step in sleep-dependent consolidation of ODP.

The mechanisms generating precise connections between specific thalamic nuclei and cortical areas remain poorly understood. Using axon tracing analysis of ephrin/Eph mutant mice, we provide in vivo evidence that Eph receptors in the thalamus and ephrins in the cortex control intra-areal topographic mapping of thalamocortical (TC) axons. In addition, we show that the same ephrin/Eph genes unexpectedly control the inter-areal specificity of TC projections through the early topographic sorting of TC axons in an intermediate target, the ventral telencephalon. Our results constitute the first identification of guidance cues involved in inter-areal specificity of TC projections and demonstrate that the same set of mapping labels is used differentially for the generation of topographic specificity of TC projections between and within individual cortical areas.

Background Recent findings indicate that certain classes of hypnotics that target GABAA receptors impair sleep-dependent brain plasticity. However, the effects of hypnotics acting at monoamine receptors (e.g., the antidepressant trazodone) on this process are unknown. We therefore assessed the effects of commonly-prescribed medications for the treatment of insomnia (trazodone and the non-benzodiazepine GABAA receptor agonists zaleplon and eszopiclone) in a canonical model of sleep-dependent, in vivo synaptic plasticity in the primary visual cortex (V1) known as ocular dominance plasticity. Methodology/Principal Findings After a 6-h baseline period of sleep/wake polysomnographic recording, cats underwent 6 h of continuous waking combined with monocular deprivation (MD) to trigger synaptic remodeling. Cats subsequently received an i.p. injection of either vehicle, trazodone (10 mg/kg), zaleplon (10 mg/kg), or eszopiclone (1–10 mg/kg), and were allowed an 8-h period of post-MD sleep before ocular dominance plasticity was assessed. We found that while zaleplon and eszopiclone had profound effects on sleeping cortical electroencephalographic (EEG) activity, only trazodone (which did not alter EEG activity) significantly impaired sleep-dependent consolidation of ocular dominance plasticity. This was associated with deficits in both the normal depression of V1 neuronal responses to deprived-eye stimulation, and potentiation of responses to non-deprived eye stimulation, which accompany ocular dominance plasticity. Conclusions/Significance Taken together, our data suggest that the monoamine receptors targeted by trazodone play an important role in sleep-dependent consolidation of synaptic plasticity. They also demonstrate that changes in sleep architecture are not necessarily reliable predictors of how hypnotics affect sleep-dependent neural functions.

Current behavioural evidence indicates that sleep plays a central role in memory consolidation. Neural events during post-learning sleep share key features with both early and late stages of memory consolidation. For example, recent studies have shown neuronal changes during post-learning sleep which reflect early synaptic changes associated with consolidation, including activation of shared intracellular pathways and modifications of synaptic strength. Sleep may also play a role in later stages of consolidation involving propagation of memory traces throughout the brain. However, to date the precise molecular and physiological aspects of sleep required for this process remain unknown. The behavioural effects of sleep may be mediated by the large-scale, global changes in neuronal activity, synchrony and intracellular communication that accompany this vigilance state, or by synapse-specific ‘replay’ of activity patterns associated with prior learning.

Additional publications

For a complete list of publications: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1081-9680