Early British record labels 1898-1926: V

Valkyrie | Velvet Face | Venus | Vesper | Victorious | Victory | Vielophone | Vitaphone | Vivaphone | Vocalion, Aeolian-Vocalion | Vox | Vox Humana

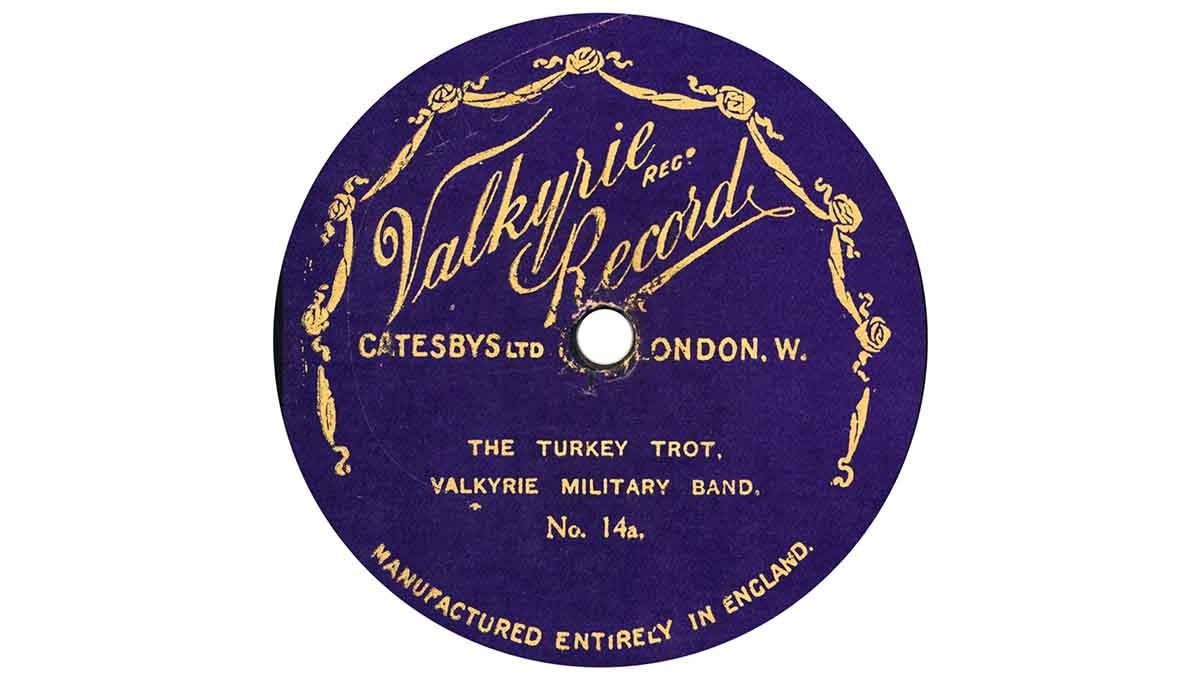

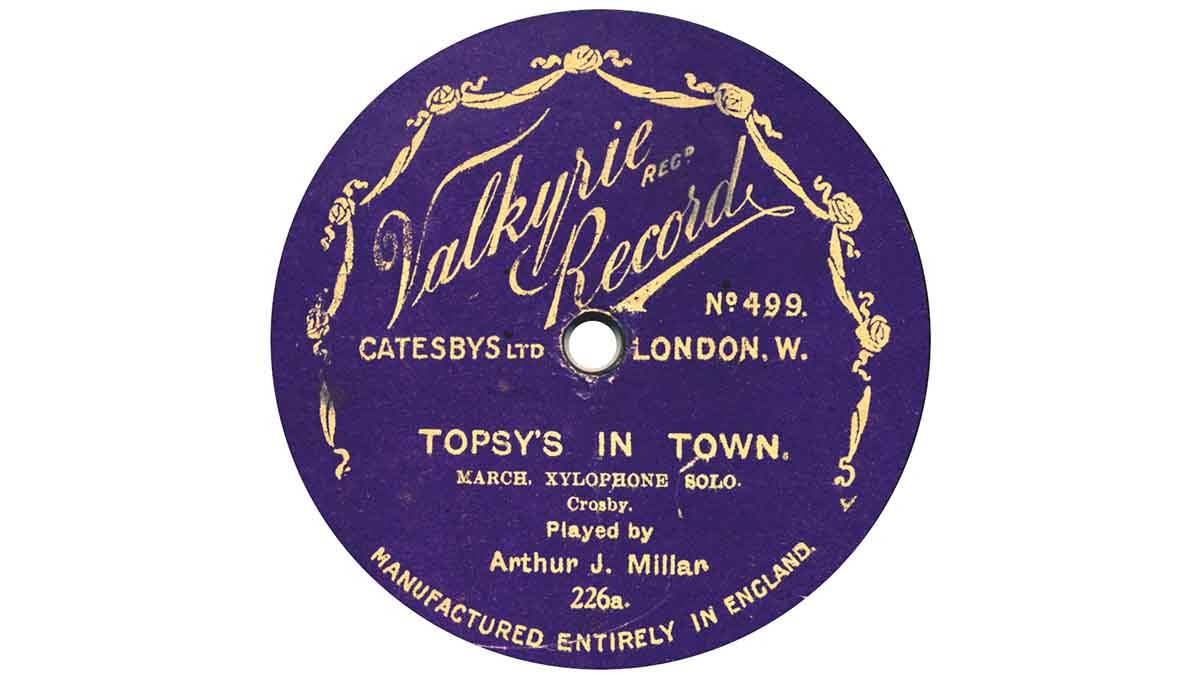

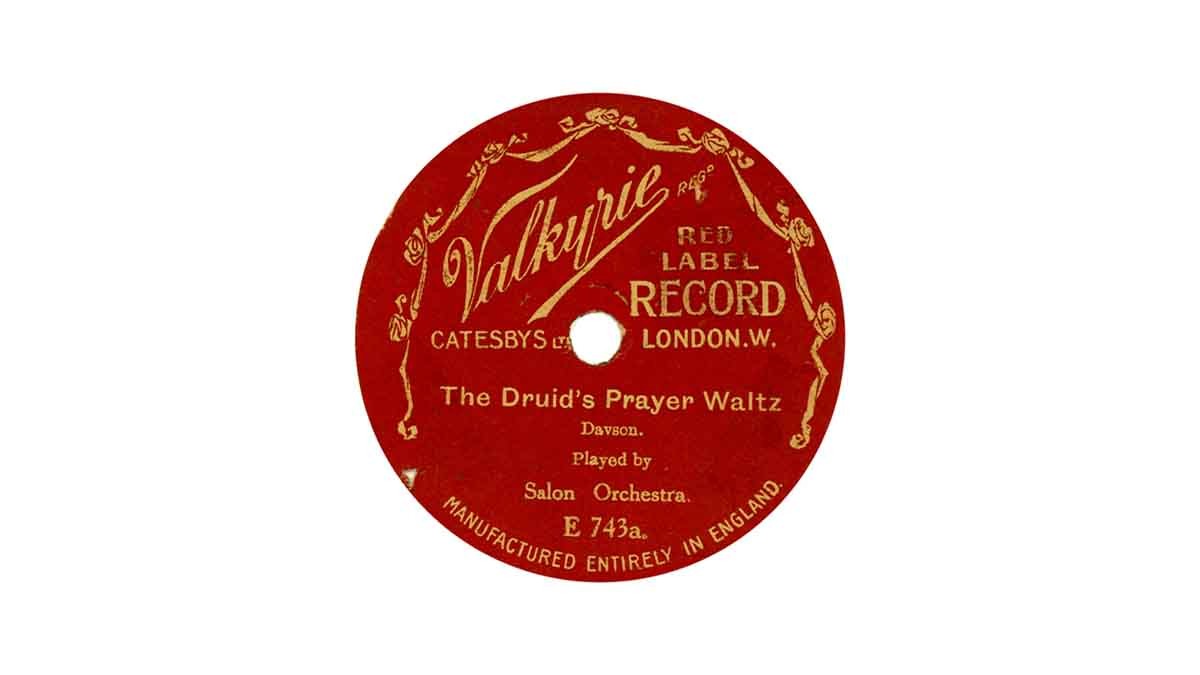

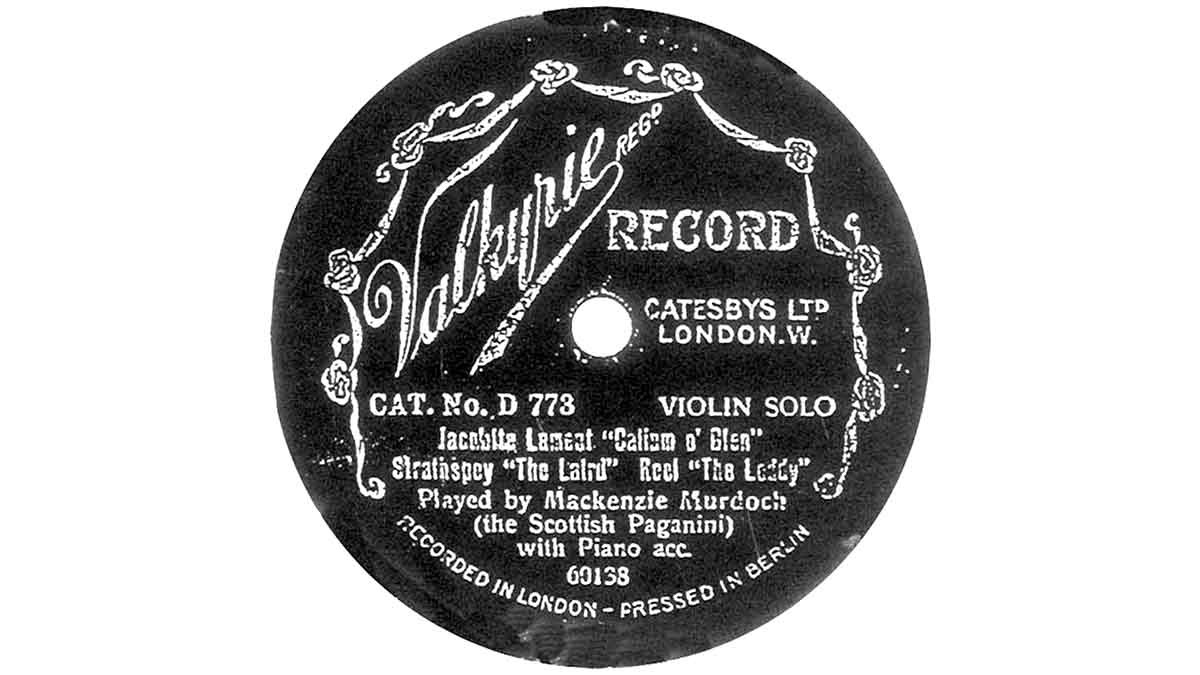

Valkyrie

See Frank Andrews, HD 181, 1991. Catesby’s London department store was in the Tottenham Court Road, with various branches nearby. Frank tells us that the violet labels came first, and were pressed from Beka masters, either at Crystalate in Kent, or possibly at the Lindström/Odéon/Beka factory in Hertford. They may have appeared for the Christmas 1912 trade. Blue and red labels came later, and are drawn from Jumbo. Jumbos had always been pressed by Crystalate until the Lindström/Fonitipia factory opened, right around this time, hence the ‘either – or’. Jumbos and their derivatives, including Valkyrie, would inevitably end up being pressed in Hertford. Thanks to recent research by Mike Langridge, Bill Dean-Myatt and Mike Thomas, the numerical series is currently thought to be continuous. The D- and E- prefixes that occur on later issues must have some other, unknown significance . The catalogue numbers run from 1 to just over 1050 with the possibility of two or three lacunae. A few early D’s are from Homophon masters, which is most singular, and thus far unexplained. The label appears to have terminated perhaps during 1915, to judge from the highest master numbers, which date from late 1914, and contain much Patriotic repertoire. (The Great War began in August 1914.)

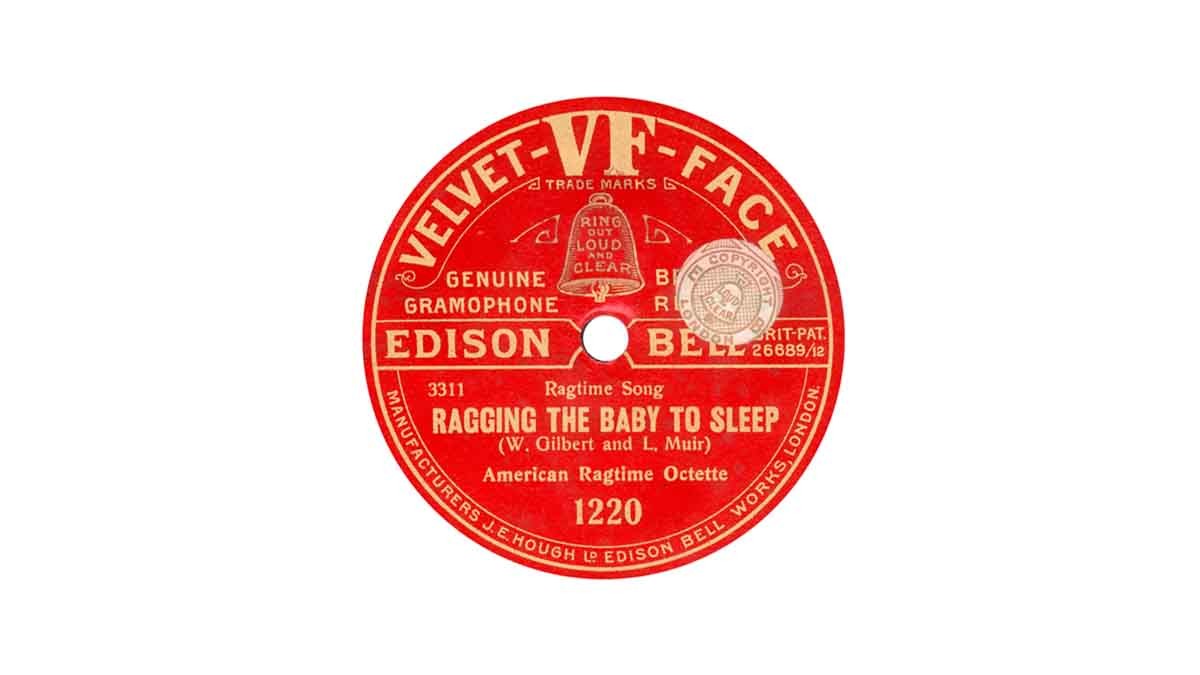

Velvet Face

The C.L.P.G.S. Reference Series booklet No.41 carries a detailed written history of Edison Bell, by Frank Andrews and Bill Dean-Myatt. It contains a CD-ROM having nearly 17,000 Edison Bell masters (Bell Disc, Electron, Radio &c as well as Winner) listed in a MS Excel file, fully searchable & sortable. Go to C.L.P.G.S. for more info & other such ‘new wave’ label listings. Frank Andrews’ earlier reseach appeared in HD 141, 142, 143, 145, 1984-1985.

Velvet-Face discs were announced in September 1910, but did not appear until November. They were supposed to play longer than the Bell-Disc, which was the ‘normal’ EB disc record, which had been put out in 1908. Also, they were to have a higher class repertoire. They had red labels – already an ‘industry standard’ for the celebrity record. But in June 1911, a number of operatic records (some single-sided) appeared actually described as ‘Velvet-Face Celebrity Record’. Alas, these are very rare. New Velvet-Face issues were not made after about October 1914, though a standing catalogue was kept available. After the war, the label was reincarnated under the inspired direction of Joseph Batten, now the artistic head of ‘Edison Bell’. The exalted repertoire envisaged by ‘Joe’ Batten (already a veteran ‘recording expert’, composer, arranger & pianist), plus the sound quality he achieved, set standards unprecedented in the long history of ‘Edison Bell’, and indeed the British recording industry itself. Justly famous is the Velvet-Face recording première of Elgar’s Oratorio ‘The Dream of Gerontius’. Mighty HMV thought was too demanding to record – in spite of the fact that Sir Edward Elgar himself was under contract to them. Naturally, Elgar could not associate himself directly with a rival company, but it is known that secretly, he approved of Batten’s project. With a 500 catalogue series for 12″ discs, and stepping back to 1000 for 10″ issues, their refined violet & gold labels were carefully printed on high-quality textured paper; the whole concept of the new era of Velvet-Face under Batten’s direction was ‘pure class’ – the like of which had never been seen since the glory days of Fonitipia, fifteen years before. The Velvet Face label continued beyond our time period; its later output was recorded electrically.

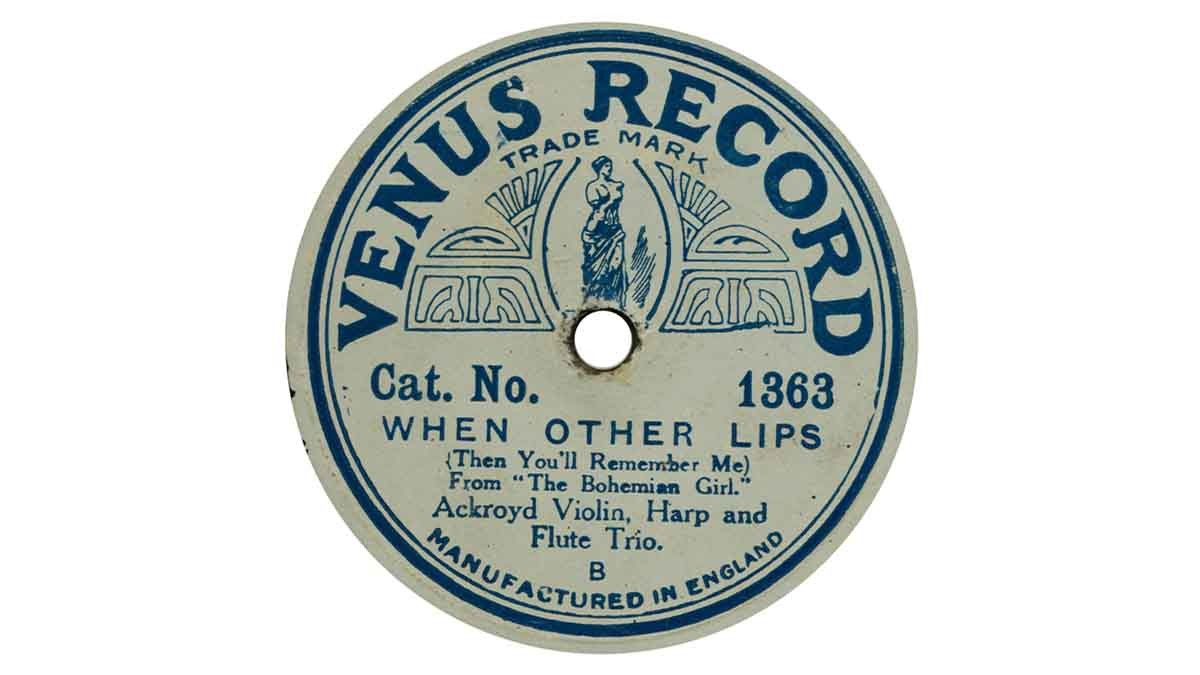

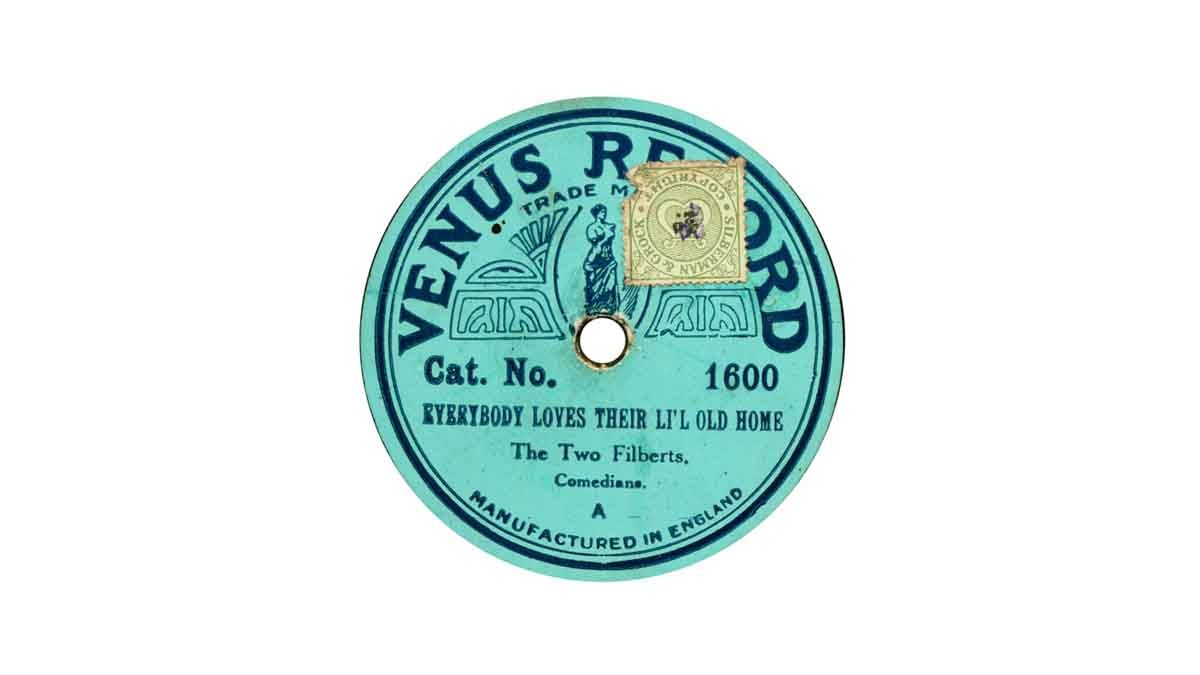

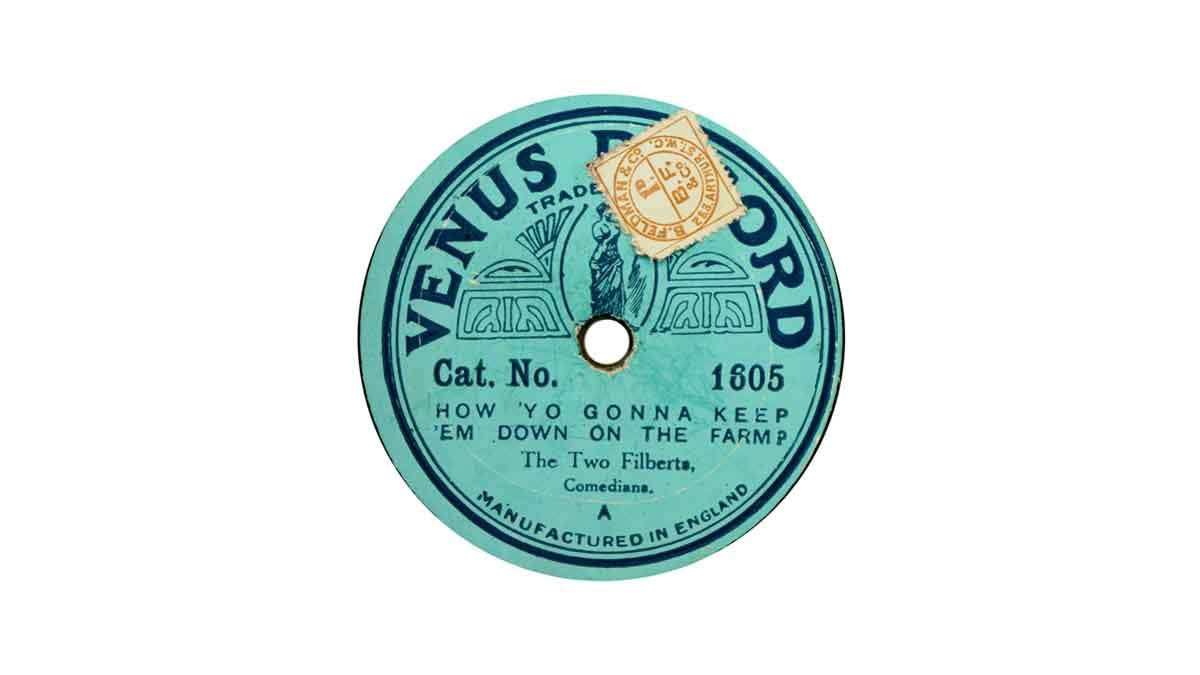

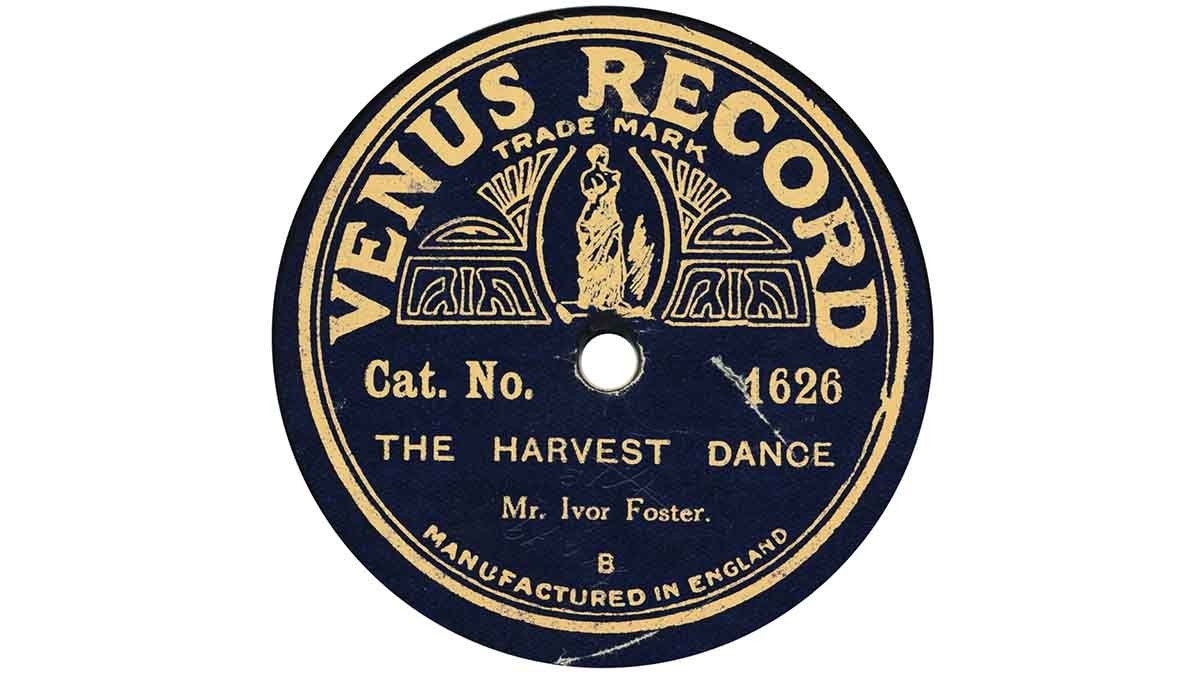

Venus

See TMR 96, 1997. Venus was a linear descendant of Jumbo. Jumbo had to disappear when the Lindström/Fonitipia factory at Hertford – indeed the whole business – was confiscated, in 1916, by the government under the ‘Trading With the Enemy Act’ 1914. This had been more rigorously applied as the war went on. Firms such as Lindström and its subsidiary Beka had at first been allowed to continue trading after August 1914 because they were British companies, properly established under British Company Law, and doubtless with British directors. But they were still, in effect, branches of German companies – hence their compulsory démise. A new company, the Hertford Record Co. was set up, under the supervision of the Board of Trade, to utilise the factory and its assets. This later came under the control of Columbia. It so happened the Jumbo record was an extremely popular ‘line’ and sold well. It was therefore inadvisable to simply scrap it. One of the registered trade marks that Columbia had up its sleeve was ‘Venus’; the rest is obvious… Apart from the name, relatively little changed. The label design was similar, and the catalogue numbers continued as before. When good-selling Jumbos ran out of stock, they were re-pressed as Venus. Therefore the labels overlap. The highest Jumbo I have is 1567; the lowest Venus, amazingly, is 781. But that reached far back into standard repertoire – it is a military band playing ‘Old Comrades March’. The normal overlap between Jumbos & Venuses would be much smaller, and probably not every late Jumbo would be reincarnated as a Venus. The label was around from say 1917-18 to probably 1920.

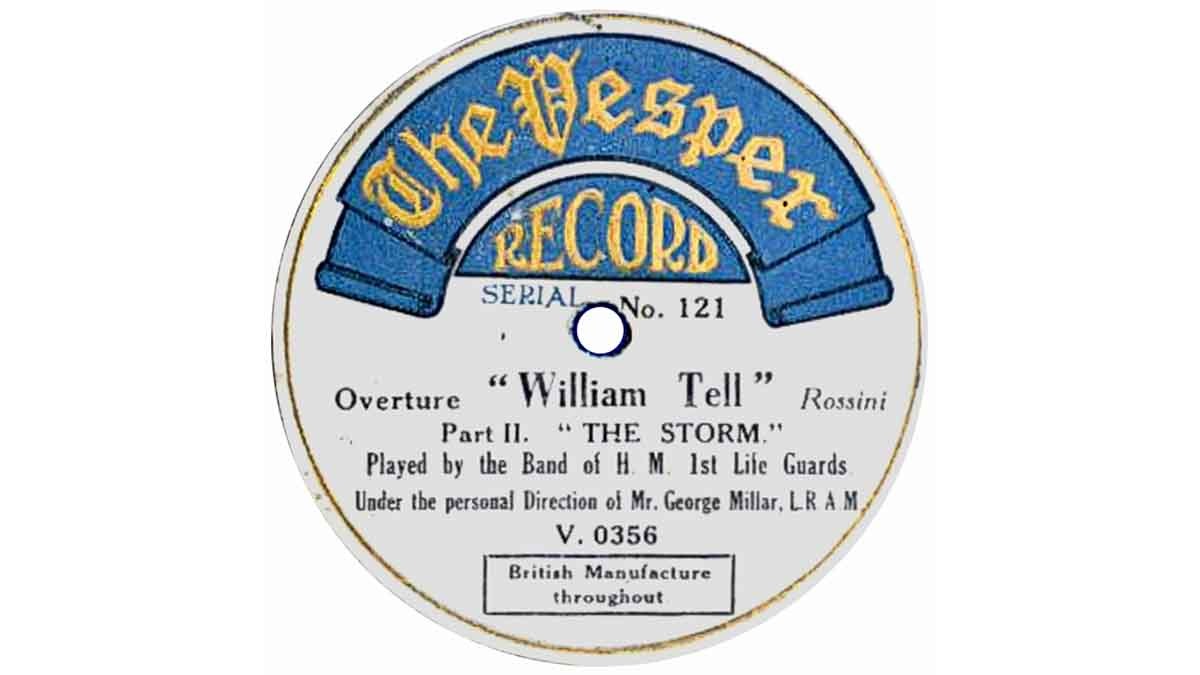

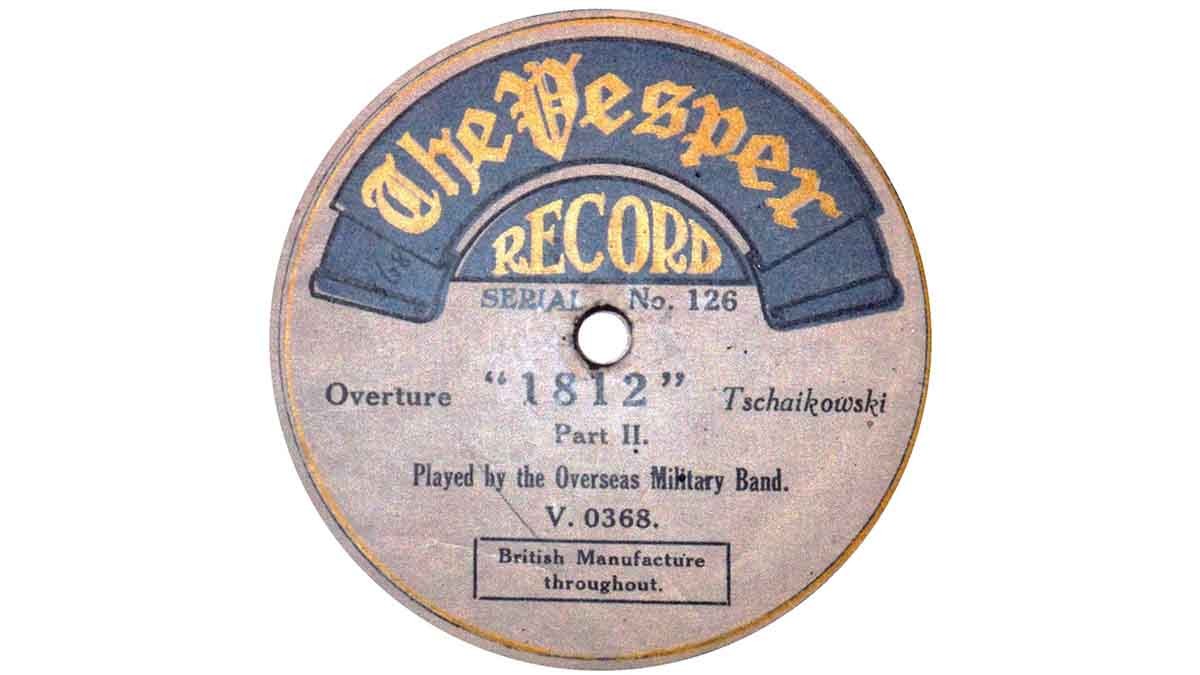

Vesper

See Frank Andrews, FTR37, 2011, p280. In a useful appendix to this, the second of his long and very informative articles on Williams Ditcham’s Bulldog records, Frank adds that certain Bulldog masters appeared on the Vesper label. Vesper was the name used by The Standard Manufacturing Co. Ltd. for their new line of gramophones, launched about 1920. Like many manufacturers of gramophones, they wanted records to go with them, and evidently Bulldog were happy to supply these. They were pressed – as were all Bulldogs – by Crystalate, at their factory in or near Tonbridge, Kent. I once had a Vesper gramophone. It was ‘bitsa’ – that is, something made up from bits of this and bits of that, but was mostly Vesper. The tone arm was certainly original, and very subtle, being made out of ebonite, the small end being telescopic into the larger. Both sections were parallel, thus avoiding the Gramophone Co’s patent for a tapering arm. It sounded very well indeed. I have quite a few Bulldog discs, but have never seen a Vesper Record, because both Vesper gramophones and their eponymous records are extremely scarce. Incidentally, the master number V.0356 is the Vesper version of 356 – which was on Bulldog 618, issued April 1917.

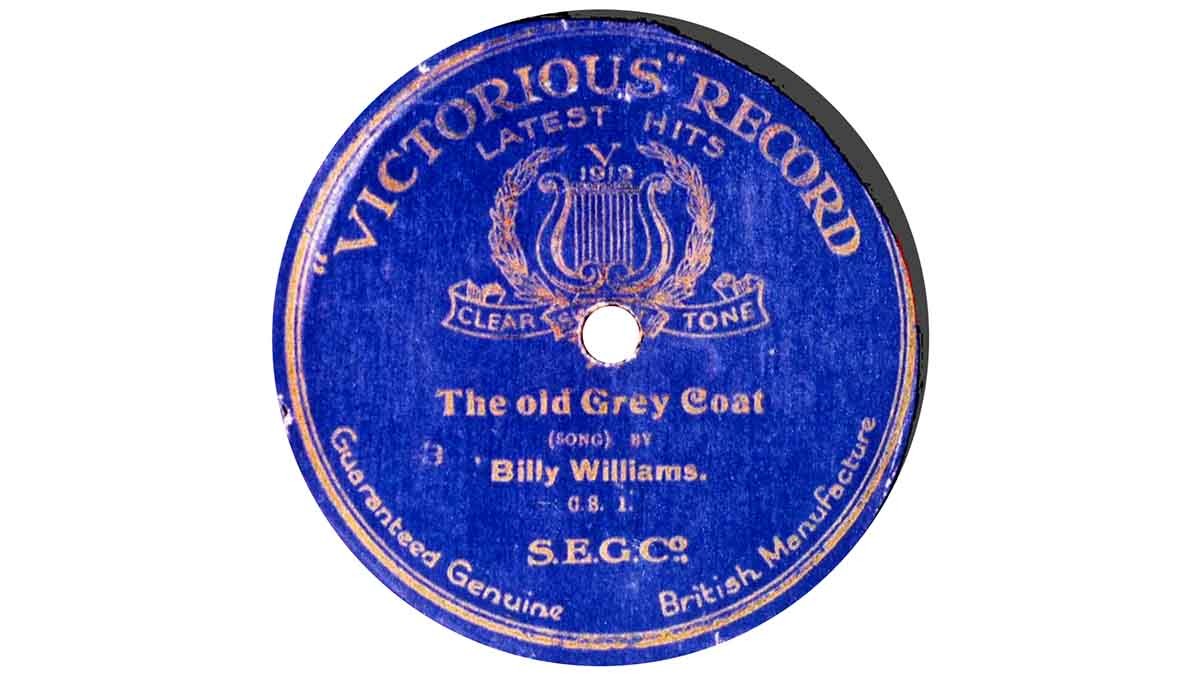

Victorious

By courtesy of Bill Dean-Myatt comes this extremely rare label. At this time no information is available as to the proprietor other than ‘S.E.G. Co.’, or the manufacturer. However, the label design incorporates the date of 1919 (or possibly 1918) which explains the label name as well as placing it in our time scale.

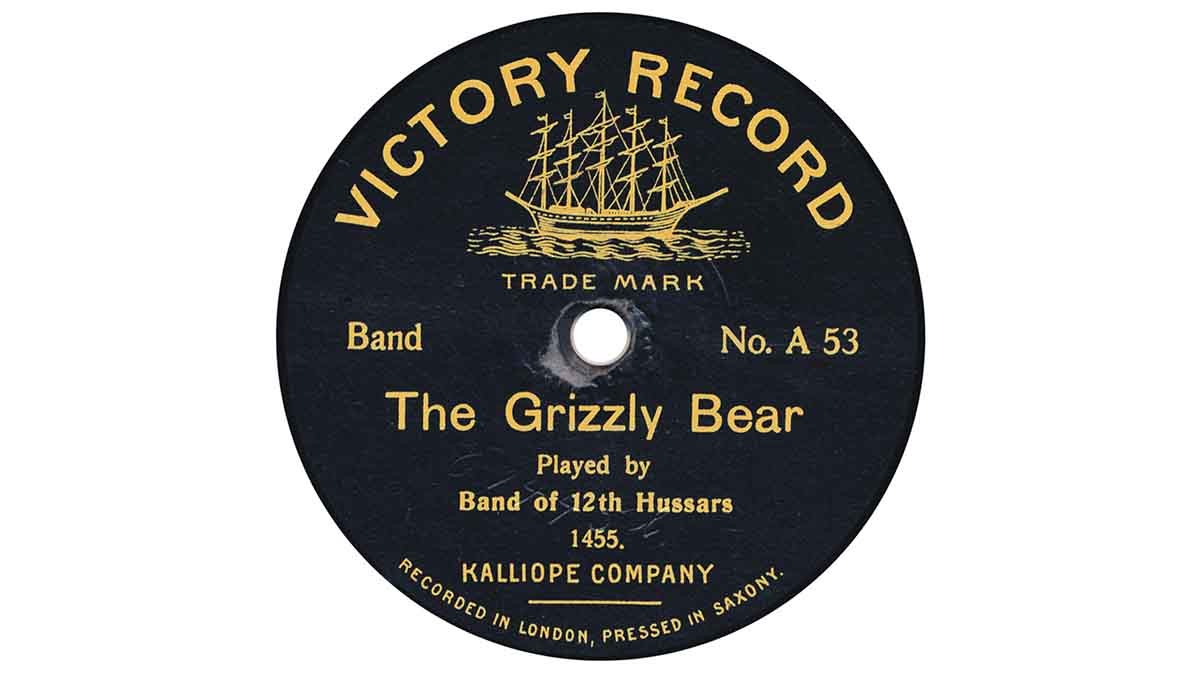

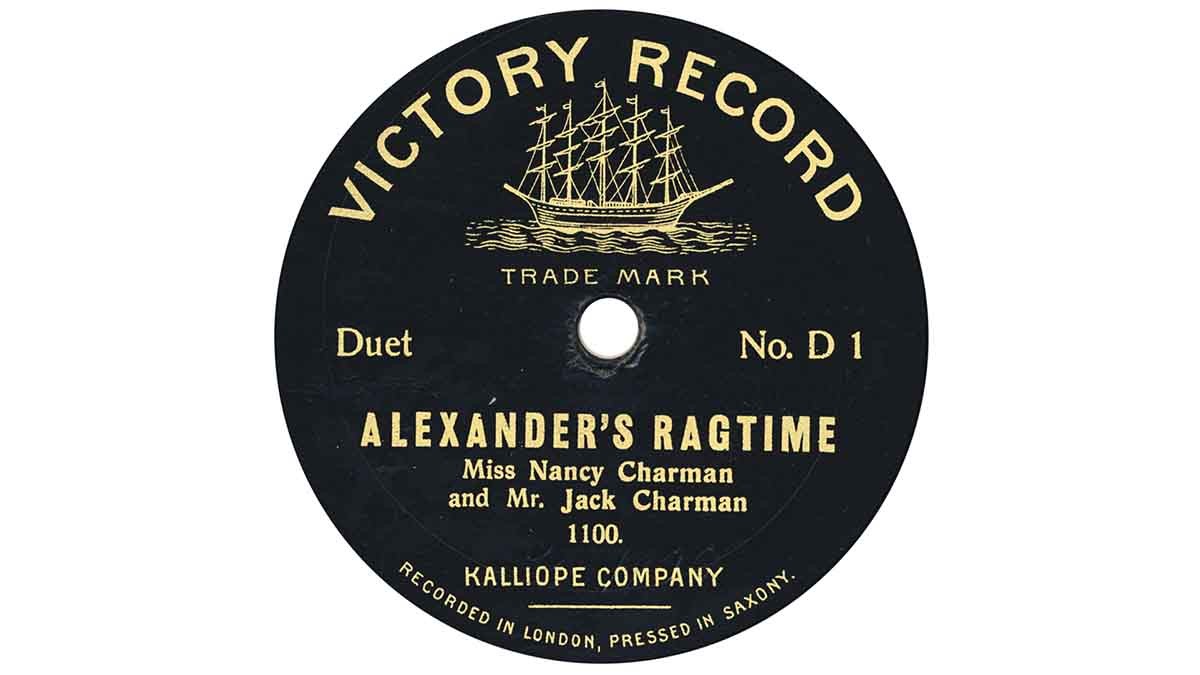

Victory

See Frank Andrews, HD 229 re. Diploma, and above all FTR 75, 1988, for a detailed history of J.L. Blum and his labels. Victory is a ‘triplet’ with Stella and Diploma records. All three were labels of the factor Leonard Joseph Blum, who traded at first from 89 Chiswell St., London, and later from premises in Old St., London E.C. Most were made by Kalliope in Dresden, with the exception of earlier Diplomas (Edison Bell); and Blum next used a factory in Prussia after he had fallen out with Kalliope. The 12″ Victory 17 seen here is an example, stating ‘Reproduced in Prussia’. Later, Blum seems to have taken a stake in the Disc Record Company of Harrow, Middx, and from early 1914 all his labels were pressed there, until the démise of the DRC in late 1914/early 1915. However, Harrow-pressed Victorys are very scarce. The label was around from about 1911 to 1914. Blum had several other labels too. Collectively, somewhere around 600 issues have been noted on Victory, Stella and Diploma by Frank – he feels they may even have all appeared on all three labels. However, Blum encountered a problem with using the name Stella (q.v.) and had to relinquish that name as Pathé had already registered it. Existing Stellas were not wasted – a perforated slip was printed ‘Victory’ & affixed over the offending word, as you see above. The catalogue prefix A was for bands; B for ‘ballad’ songs; C for comic songs; D for duets, E for sacred and F for instrumental solos – but repertoire is known to cross over occasionally. Q: Why have three labels ‘all the same’? A: I imagine it was to allow Blum to supply at least three retailers in the same town with his product, so that the retailers would not appear to be – unduly – competing with each other? They sold tolerably well and so turn up to this day from time to time.

Vielophone

A label sold in India by the eponymous company in Bombay. They were, however, manufactured in the U.K. by J E Hough & Co. – more casually known as ‘Edison Bell’. The punched-out round copyright stamps (these were unique to Edison Bell, and nobody knows why they did it) were presumably attached in the U.K. before export. The march ‘Action Front’ appeared on Winner 2252, which was issued in January 1913. However, the label design of this Vielophonespeaks clearly of ~1925 rather than 1913. Still, that would not have mattered, as in 1925 Winners were still being recorded by the mechanical (so-called acoustic) process. The sound quality of Winners was pretty good in 1913; and the ‘Royal Guards Band’, though it only existed in the Edison Bell studio, was a very fine ensemble indeed, consisting of top players from the Guards regiments stationed in London. So it didn’t matter in 1925 that the recording was ‘old’. Later, Vielophones were pressed in India, but the masters were still supplied by Edison Bell. An example is shown, even though it was electrically recorded &, strictly speaking, outside the scope of these pages. (‘Gertie’ appeared on Winner 4598, issued April 1927.)

Vitaphone

See Sutton and Nauck : American Record Labels and Companies. Mainspring Press. Denver, Colorado, U.S.A., 2000. Also Ernie Bayly, TMR 54-55, p 1430, in review of Rust’s American Label Book. In late 1898, Albert Armstrong and Joseph Jones founded the American Talking Machine Company, primarily to make gramophones, but they also produced a line of 7″ (~18cm) brown discs, rather like Nicole were to make in the U.K. in 1903. They were single sided, of course. It was widely said that some or all of Vitaphone’s sides were pirated from Berliner, but apparently this has never been proved either way. Amstrong also produced discs for consumption in Europe – an image is to be found on the CD-ROM in Sutton & Nauck. Alas, although Frank Andrews confirms this in a very short note on the label, he stated simply: “1900 (label exports, American Talking Machine Co.)” Any further research he may have done has not come to light, so far. The U.S. concern was closed down by litigation late in 1900. Very few people can have ever seen a British Vitaphone disc; indeed, most people have never even heard of them!

Vivaphone

There is a website devoted to films of Cecil Hepworth. Also see John W Booth, Frank Andrews & Richard Brown, TMR 92, 1995-96. (This article may be found on the URL just given). Better still, four of Hepworth’s Vivaphone films may be seen on the British Film Institute’s website. This label was not on sale to the general public, so is quite different in status to most of the other ‘makes’ of record in these pages. The very informative article above tells us that custom pressed single-sided discs were made by various companies at the behest of Cecil Hepworth (1874-1952). He was involved in moving pictures from their very beginning, and no later than 1907 devised a system of synchronisation between a short film and a disc, thus enabling a sound film. The disc was selected first, then an actor or actors would learn the record, and were then filmed while miming to it. It is important to note that the artistes on the record were not the performers filmed, so alas there is no film of Billy Williams. Having said that, they did film some eminent people, as opposed to entertainers, miming to their own records. Distinguished statesmen such as Andrew Bonar Law and F.E. Smith (Lord Birkenhead) were so filmed. Some hundreds of films were produced altogether over a period of four years or so. His original mechanical synchronisation device was later replaced by an improved electric version, which was patented in 1910. The discs had a special ‘lead-in’ slot pressed or cut into them, to provide the original reference point. In addition, on the Columbia disc 2248 (the only disc we have been able to examine, thanks to the generosity of Steven Walker), a projectionist has stuck a piece of elastoplast on the back of the disc near the lead-in slot to facilitate locating it in the dark. Additionally, the slot has been highlighted with gold metallic paint; though whether this was applied at Hepworths, or by our versatile and intrepid projectionist is not known. The rarity of the discs today (even Frank Andrews knew of only a handful) is probably because (a) rather obviously, they were never sold to the public; and (b) once the system was obsolete, it was very obsolete indeed – so probably everything was junked.

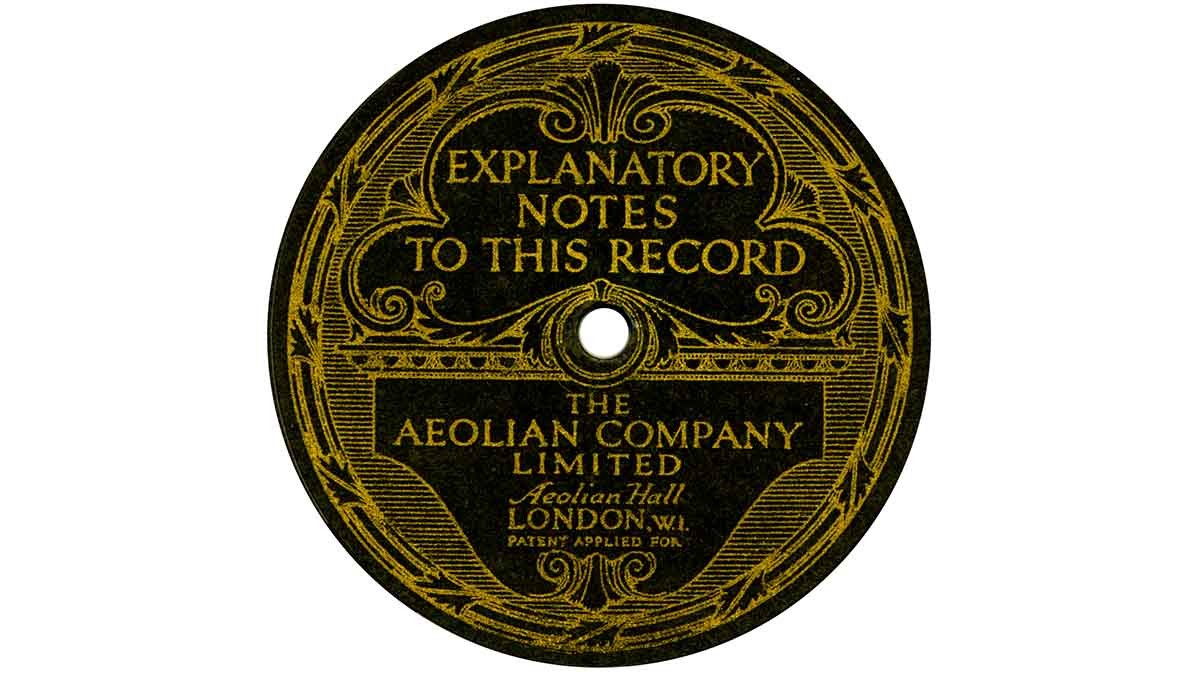

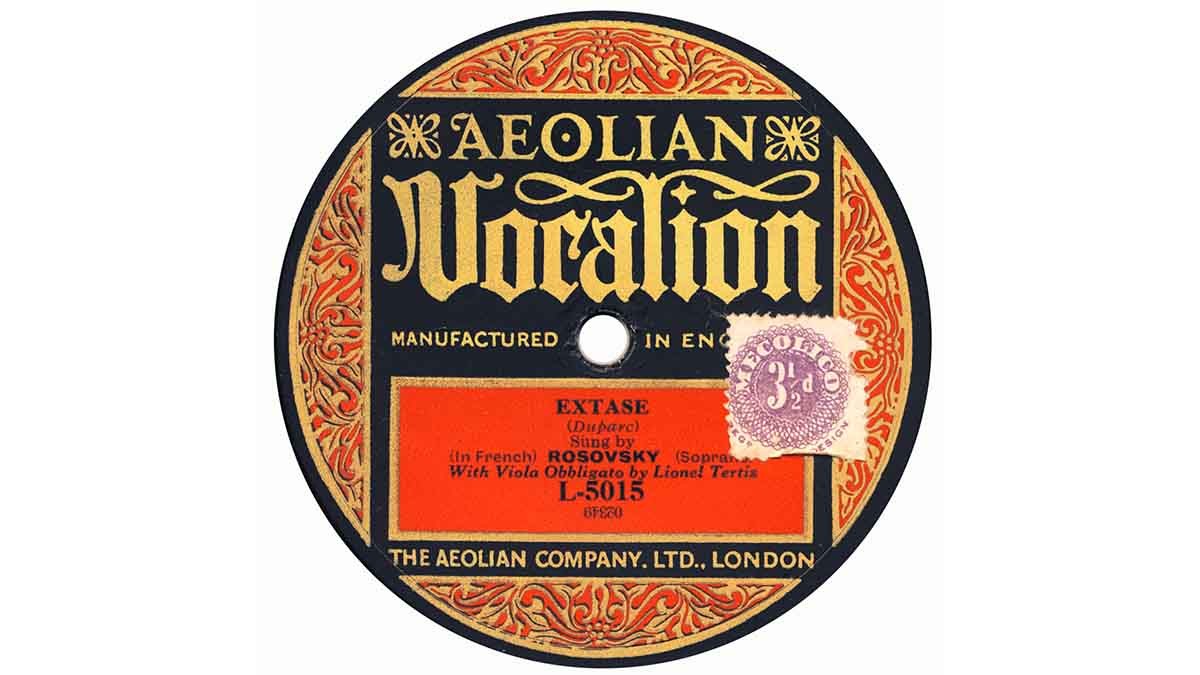

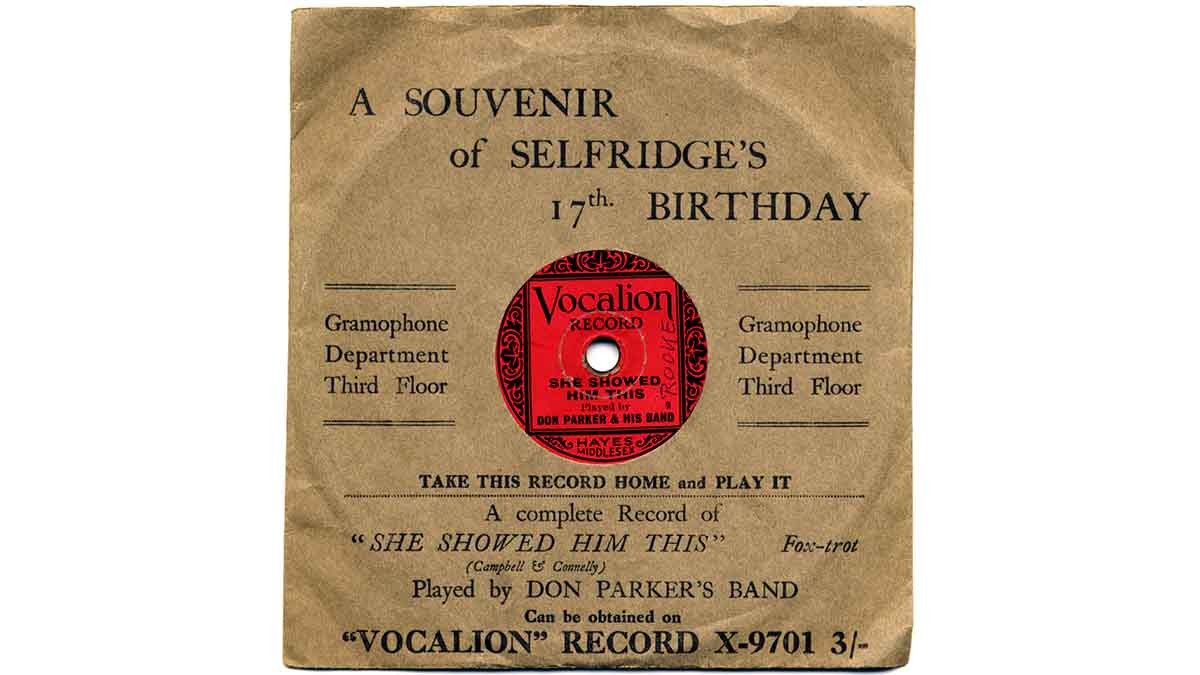

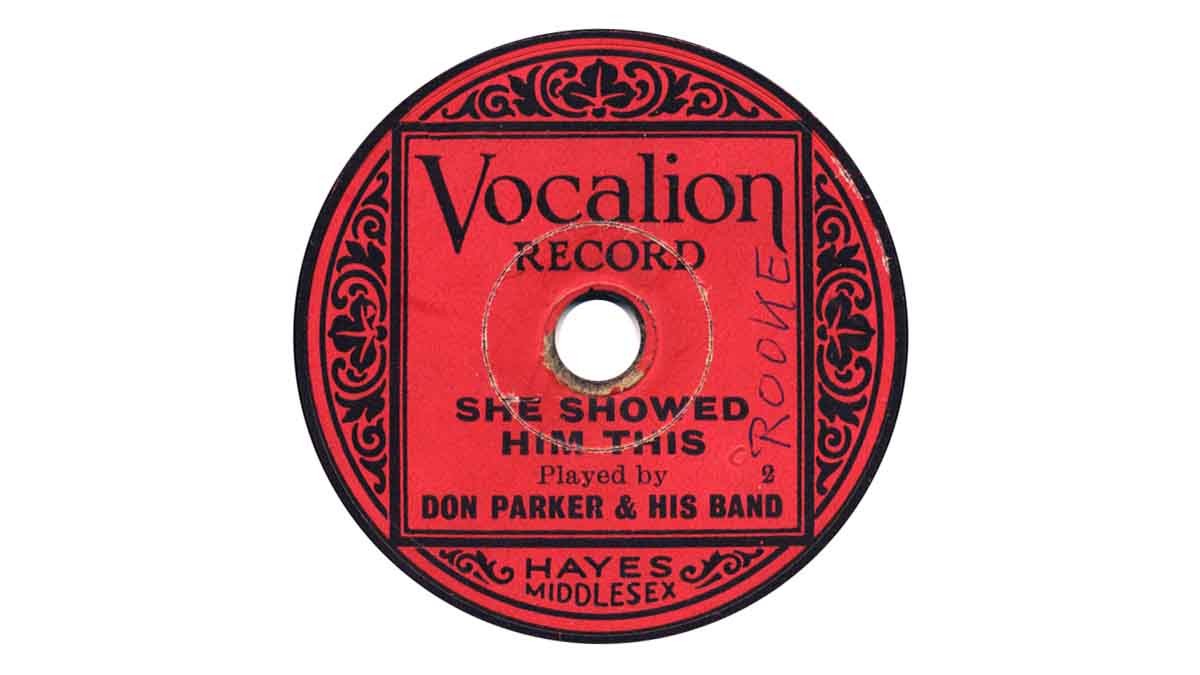

Vocalion, Aeolian-Vocalion

Just published is a major CLPGS project on this label and its many satellites. Indefatigably correlated by Keith Harrison, a 60-page A5 book gives the extensive history, and comes with a CD-ROM, with searchable databases of over 16,000 entries. Go to www.clpgs.org.uk and scroll down to RS42 to get your copy. The nucleus of this work was by Frank Andrews in HD 116, 117, 118. 1980-81. Though their early discs are relatively elusive, the British Aeolian-Vocalion records were conceived from the beginning as a quality product. The evolution of the companies involved was complex, but all is lucidly explained in the above book. Their catalogue was ambitious, and the discs were expensive. They appeared in September 1920, a pressing plant having been built at Hayes, Middlesex. ‘Aeolian’ was a type, or system, of a wind or reed organ that originated in Australia but apparently became the property of the Orchestrelle Co. of New Jersey, U.S.A.; and ‘Vocalion’ had been the name applied to other reed organs marketed by a small U.S. concern that was also taken over by Orchestrelle in the 1890s, but languished until they decided to make disc records. Then, they thought that ‘Vocalion’ was a pretty good name for a disc record. Which it is, isn’t it? There were a variety of label colours. The most prestigious were pink, and these carried a spoken commentary or analysis of the work pressed onto the reverse, bearing the black & gold label above. Even if there was no commentary, a logo and legend, 5.5″ (14cm) in diameter, was usually pressed into the back of the disc. Another Vocalion venture was an early long-playing record, using the Pemberton-Billings ‘World’ record system (q.v.) with constant groove velocity. This was an unsuccessful venture, and the Vocalion long-players are even scarcer than the World discs. Thanks to Robert Girling for supplying an example. Besides all this, Vocalion had a cheaper label, ACO, and also pressed Beltona, Guardsman, Coliseum, Scala, Homochord, Ludgate, Meloto, Citizen, Adelphi, Cymot and others, for some (or all) of their existence.

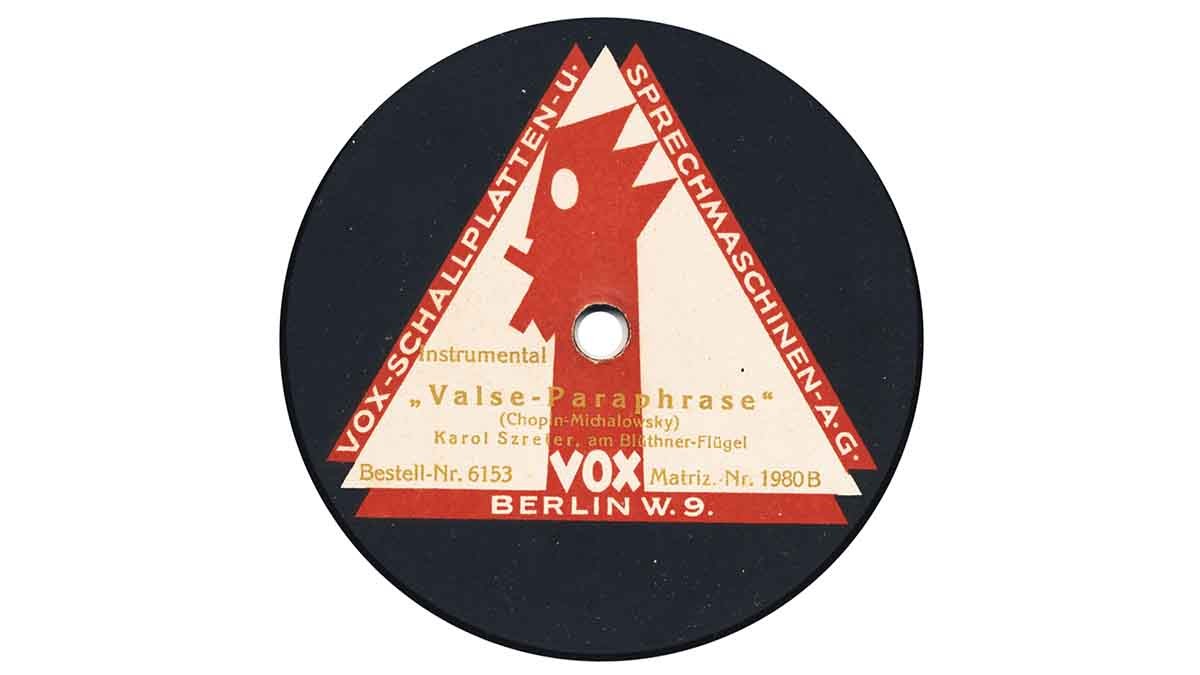

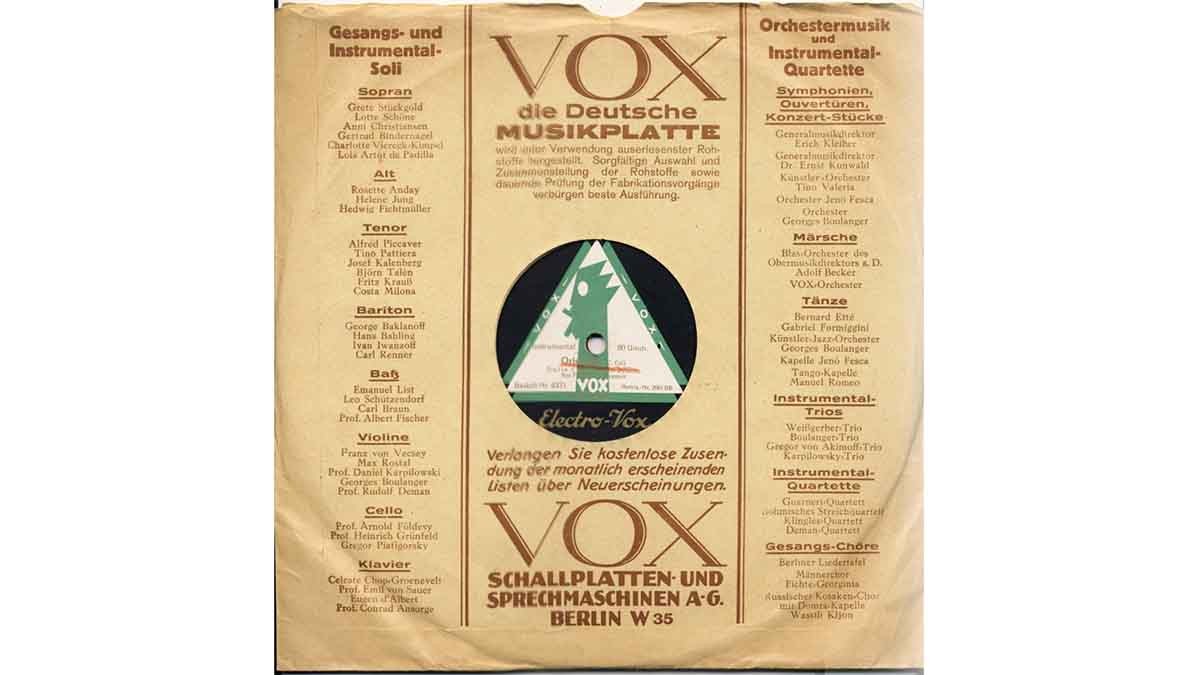

Vox

Vox was a German label which was founded in 1923. William E Barnett of Westcliffe-on-Sea, Essex, is known to have been the import agent of this label into the U.K. from 1925; its distinctive trade mark had indeed been registered in this country. However, if they were only imported after electrical recording had been adopted by Vox, they do not count as a ‘British Label’ within the terms of this site, since we deal only with mechanically recorded discs. (Vox was wound up in 1927, and its factory taken over by the British Crystalate concern, who used it to manufacture records for the German market, and possibly also for the French.)

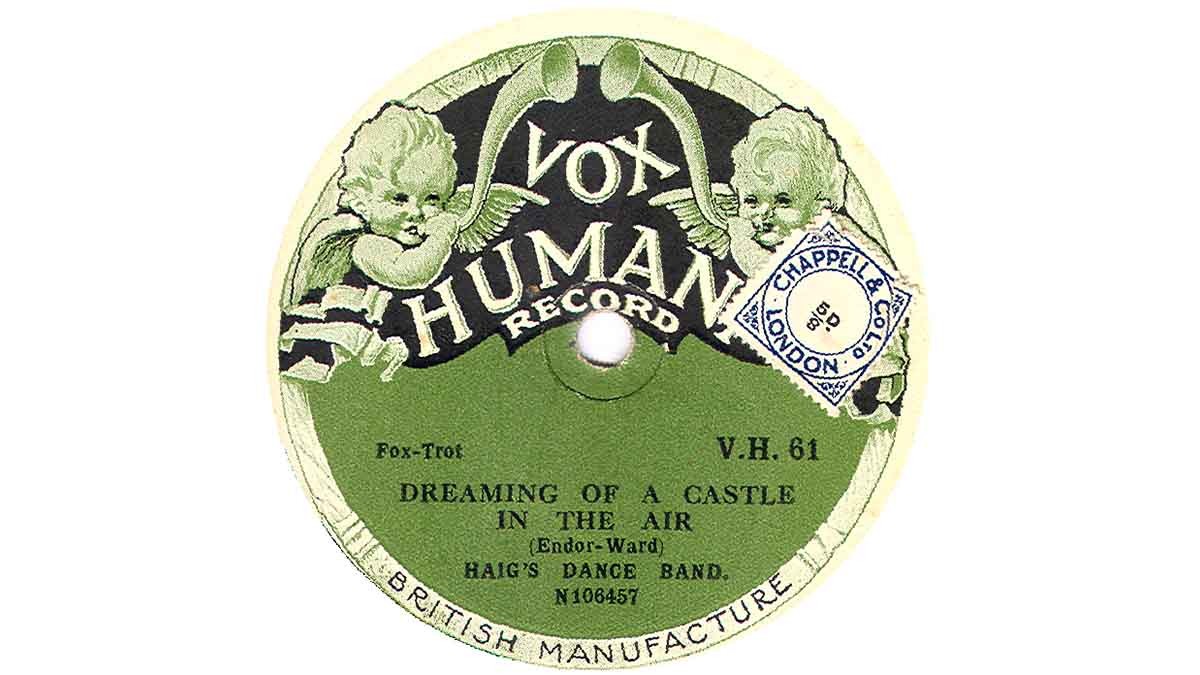

Vox Humana

This marque with its delightful label design was made in the U.K. by Pathé and exported for sale in Australia. Just under 70 discs were issued in the VH-series, in the mid 1920s. Although many of the sides were pretty contemporary, some older standard repertoire was called upon: one banjo solo, by Olly Oakley, was first issued on centre-start Pathé in March 1913. It is thought that all the sides on Vox Humana were probably recorded mechanically, though some later ones might have been made under the electrical process. Like the related Pathé product Grand Pree, also made solely for Australia, all the issues were apparently under pseudonyms.