Professor Derk-Jan Dijk

Academic and research departments

School of Biosciences, Surrey Sleep Research Centre, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences.About

Biography

Derk-Jan Dijk PhD, FRSB, FMedSci, is Professor of Sleep and Physiology, Distinguished Professor at the University of Surrey, Director of the Surrey Sleep Research Centre. He has been a Royal Society-Wolfson Research Merit Award holder, a Senior Research Associate in the Institute of Pharmacology at the University of Zurich, an Assistant Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School, and an Associate Neuroscientist in the Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston.

Dr Dijk has 40 years of experience in clinical sleep research. His current research interests include the circadian and homeostatic regulation of sleep; the contribution of sleep to brain function in healthy ageing and dementia; the role of circadian rhythmicity in sleep regulation; identification of novel-biomarkers for sleep debt status and circadian rhythmicity, susceptibility to the negative effects of sleep loss; understanding age and sex related differences in sleep physiology and sleep disorders. His research has been or is is funded by the Dementia Research Institute, the Biotechnology and Biological Science Research Council, the Wellcome Trust, The Air Force Office of Scientific Research, Philips Lighting and several major pharmaceutical companies.

Dr Dijk has published more than 300 research and review papers in the area of sleep and circadian rhythms. Dr Dijk is invited frequently to speak at international sleep meetings and he has given opening and plenary lectures for the joint meeting of the Canadian Sleep Society, American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society, The European Sleep Research Society and the Hong Kong Sleep Medicine Society.

Dr Dijk has served as an Associate and Deputy Editor to SLEEP and Editor of the Journal of Sleep Research. He also serves as consultant to the pharmaceutical industry.

Areas of specialism

News

In the media

ResearchResearch interests

Sleep is an important determinant of wellbeing and health. Understanding how sleep is regulated and how it contributes to mental and physical health, cognition and well-being is at at the centre of the research in the Surrey Sleep Research Centre. Using approaches ranging from genetics to behavioural assessments, and with an emphasis on sleep physiology, EEG analysis and circadian rhythms, the functional significance of sleep is investigated across the adult life span.

Research interests

Sleep is an important determinant of wellbeing and health. Understanding how sleep is regulated and how it contributes to mental and physical health, cognition and well-being is at at the centre of the research in the Surrey Sleep Research Centre. Using approaches ranging from genetics to behavioural assessments, and with an emphasis on sleep physiology, EEG analysis and circadian rhythms, the functional significance of sleep is investigated across the adult life span.

Supervision

Postgraduate research supervision

I supervise on the following courses:

Sustainable development goals

My research interests are related to the following:

Publications

The two-process model (2pm) of sleep regulation is a conceptual framework and consists of mathematical equations. It shares similarities with models for cardiac, respiratory and neuronal rhythms and falls within the wider class of coupled oscillator models. The 2pm is related to neuronal mutual inhibition models of sleep-wake regulation. The mathematical structure of the 2pm, in which the sleep-wake cycle is entrained to the circadian pacemaker, explains sleep patterns in the absence of 24 h time cues, in different species and in early childhood. Extending the 2pm with a process describing the response of the circadian pacemaker to light creates a hierarchical entrainment system with feedback which permits quantitative modelling of the effect of self-selected light on sleep and circadian timing. The extended 2pm provides new interpretations of sleep phenotypes and provides quantitative predictions of effects of sleep and light interventions to support sleep and circadian alignment in individuals, including those with neurodegenerative disorders.

Mechanisms regulating human sleep and physiology have evolved in response to rhythmic variation in environmental variables driven by the Earth’s rotation around its axis and the Sun. To what extent these mechanisms are operable in vulnerable people who are primarily exposed to the indoor environment remains unknown. We analyzed 26 523 days of data from outdoor and indoor environmental sensors and a contactless behavior-and-physiology sensor tracking bed occupancy, heart, and breathing rate in 70 people living with dementia. Indoor light and temperature, sleep timing, duration, and fragmentation, as well as the timing of the heart rate minimum, all varied across seasons. Beyond the effects of season, higher bedroom temperature and less bright indoor daytime light are associated with more disrupted sleep and higher respiratory rate. This sensitivity of sleep and physiology to ecologically relevant variations in indoor environmental variables implies that implementing approaches to control indoor light and temperature can improve sleep.

Biomarkers are valuable tools in a wide range of human health areas including circadian medicine. Valid, low-burden, multivariate molecular approaches to assess circadian phase at scale in people living and working in the real world hold promise for translating basic circadian knowledge to practical applications. However, standards for the development and evaluation of these circadian biomarkers have not yet been established, even though several publications report such biomarkers and claim that the methods are universal. Here, we present a basic exploration of some of the determinants and confounds of blood-based biomarker development for suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) phase by reanalysing publicly available data sets. We compare performance of biomarkers based on three feature-selection methods: Partial Least Squares Regression, ZeitZeiger, and Elastic Net, as well as performance of a standard set of clock genes. We explore the effects of training sample size and the impact of the experimental protocols from which training samples are drawn and on which performance is tested. Approaches based on small sample sizes used for training are prone to poor performance due to overfitting. Performance to some extent depends on the feature-selection method, but at least as much on the experimental conditions from which the biomarker training samples were drawn. Performance of biomarkers developed under baseline conditions does not necessarily translate to protocols that mimic real-world scenarios such as shiftwork in which sleep may be restricted or desynchronized from the endogenous circadian SCN phase. The molecular features selected by the various approaches to develop biomarkers for the SCN phase show very little overlap although the processes associated with these features have common themes with response to steroid hormones, that is, cortisol being the most prominent. Overall, the findings indicate that establishment of circadian biomarkers should be guided by established biomarker-development concepts and foundational principles of human circadian biology.

Sleep disorders are a prevalent problem among older adults, yet obtaining an accurate and reliable assessment of sleep quality can be challenging. Traditional polysomnography (PSG) is the gold standard for sleep staging, but is obtrusive, expensive, and requires expert assistance. To this end, we propose a minimally invasive single-channel single ear-EEG automatic sleep staging method for older adults. The method employs features from the frequency, time, and structural complexity domains, which provide a robust classification of sleep stages from a standardised viscoelastic earpiece. Our method is verified on a dataset of older adults and achieves a kappa value of at least 0.61, indicating substantial agreement. This paves the way for a non-invasive, cost-effective, and portable alternative to traditional PSG for sleep staging.

Circadian clocks drive cyclic variations in many aspects of physiology, but some daily variations are evoked by periodic changes in the environment or sleep–wake state and associated behaviors, such as changes in posture, light levels, fasting or eating, rest or activity and social interactions; thus, it is often important to quantify the relative contributions of these factors. Yet, circadian rhythms and these evoked effects cannot be separated under typical 24-h day conditions, because circadian phase and the length of time awake or asleep co-vary. Nathaniel Kleitman’s forced desynchrony (FD) protocol was designed to assess endogenous circadian rhythmicity and to separate circadian from evoked components of daily rhythms in multiple parameters. Under FD protocol conditions, light intensity is kept low to minimize its impact on the circadian pacemaker, and participants have sleep–wake state and associated behaviors scheduled to an imposed non-24-h cycle. The period of this imposed cycle, Τ , is chosen so that the circadian pacemaker cannot entrain to it and therefore continues to oscillate at its intrinsic period ( τ , ~24.15 h), ensuring circadian components are separated from evoked components of daily rhythms. Here we provide detailed instructions and troubleshooting techniques on how to design, implement and analyze the data from an FD protocol. We provide two procedures: one with general guidance for designing an FD study and another with more precise instructions for replicating one of our previous FD studies. We discuss estimating circadian parameters and quantifying the separate contributions of circadian rhythmicity and the sleep–wake cycle, including statistical analysis procedures and an R package for conducting the non-orthogonal spectral analysis method that enables an accurate estimation of period, amplitude and phase. This protocol describes how to design, implement and analyze the data from a forced desynchrony protocol to assess endogenous circadian rhythmicity and to separate circadian from evoked components of daily rhythms in physiology and behavior.

Study Objectives: Portable electroencephalography (EEG) devices offer the potential for accurate quantification of sleep at home but have not been evaluated in relevant populations. We assessed the Dreem headband (DHB) and its automated sleep staging algorithm in 62 older adults [age (mean±SD) 70.5±6.7 years; 12 Alzheimer’s]. Methods: The accuracy of sleep measures, epoch-by-epoch staging, and the quality of EEG signals for quantitative EEG (qEEG) analysis were compared to standard polysomnography (PSG) in a sleep laboratory. Results: The DHB algorithm accurately estimated total sleep time (TST) and sleep efficiency (SEFF) with a Symmetric Mean Absolute Percentage Error (SMAPE)

Background: Contactless sleep technologies (CSTs) hold promise for longitudinal, unobtrusive sleep monitoring in the community and at scale. They may be particularly useful in older populations wherein sleep disturbance, which may be indicative of the deterioration of physical and mental health, is highly prevalent. However, few CSTs have been evaluated in older people. Objective: This study evaluated the performance of 3 CSTs compared to polysomnography (PSG) and actigraphy in an older population. Methods: Overall, 35 older men and women (age: mean 70.8, SD 4.9 y; women: n=14, 40%), several of whom had comorbidities, including sleep apnea, participated in the study. Sleep was recorded simultaneously using a bedside radar (Somnofy [Vital Things]: n=17), 2 undermattress devices (Withings sleep analyzer [WSA; Withings Inc]: n=35; Emfit-QS [Emfit; Emfit Ltd]: n=17), PSG (n=35), and actigraphy (Actiwatch Spectrum [Philips Respironics]: n=18) during the first night in a 10-hour time-in-bed protocol conducted in a sleep laboratory. The devices were evaluated through performance metrics for summary measures and epoch-by-epoch classification. PSG served as the gold standard. Results: The protocol induced mild sleep disturbance with a mean sleep efficiency (SEFF) of 70.9% (SD 10.4%; range 52.27%-92.60%). All 3 CSTs overestimated the total sleep time (TST; bias: >90 min) and SEFF (bias: >13%) and underestimated wake after sleep onset (bias: >50 min). Sleep onset latency was accurately detected by the bedside radar (bias: 16 min). CSTs did not perform as well as actigraphy in estimating the all-night sleep summary measures. In an epoch-by-epoch concordance analysis, the bedside radar performed better in discriminating sleep versus wake (Matthew correlation coefficient [MCC]: mean 0.63, SD 0.12, 95% CI 0.57-0.69) than the undermattress devices (MCC of WSA: mean 0.41, SD 0.15, 95% CI 0.36-0.46; MCC of Emfit: mean 0.35, SD 0.16, 95% CI 0.26-0.43). The accuracy of identifying rapid eye movement and light sleep was poor across all CSTs, whereas deep sleep (ie, slow wave sleep) was predicted with moderate accuracy (MCC: >0.45) by both Somnofy and WSA. The deep sleep duration estimates of Somnofy correlated (r2=0.60; P

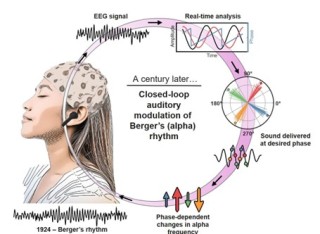

Alpha and theta oscillations characterize the waking human electroencephalogram (EEG) and can be modulated by closed-loop auditory stimulation (CLAS). These oscillations also occur during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, but their function here remains elusive. CLAS represents a promising tool to pinpoint how these brain oscillations contribute to brain function in humans. Here we investigate whether CLAS can modulate alpha and theta oscillations during REM sleep in a phase-dependent manner. We recorded high-density EEG during an extended overnight sleep period in 18 healthy young adults. Auditory stimulation was delivered during both phasic and tonic REM sleep in alternating 6 s ON and 6 s OFF windows. During the ON windows, stimuli were phase-locked to four orthogonal phases of ongoing alpha or theta oscillations detected in a frontal electrode. The phases of ongoing alpha and theta oscillations were targeted with high accuracy during REM sleep. Alpha and theta CLAS induced phase-dependent changes in power and frequency at the target location. Frequency-specific effects were observed for alpha trough (speeding up) and rising (slowing down) and theta trough (speeding up) conditions. CLAS-induced phase-dependent changes were observed during both REM sleep substages, even though auditory evoked potentials were very much reduced in phasic compared to tonic REM sleep. This study provides evidence that faster REM sleep rhythms can be modulated by CLAS in a phase-dependent manner. This offers a new approach to investigate how modulation of REM sleep oscillations affects the contribution of this vigilance state to brain function.

Background: Sleep disorders are common among the aging population and people with neurodegenerative diseases. Sleep disorders have a strong bidirectional relationship with neurodegenerative diseases, where they accelerate and worsen one another. Although one-to-one individual cognitive behavioral interventions (conducted in-person or on the internet) have shown promise for significant improvements in sleep efficiency among adults, many may experience difficulties accessing interventions with sleep specialists, psychiatrists, or psychologists. Therefore, delivering sleep intervention through an automated chatbot platform may be an effective strategy to increase the accessibility and reach of sleep disorder intervention among the aging population and people with neurodegenerative diseases. Objective: This work aims to (1) determine the feasibility and usability of an automated chatbot (named MotivSleep) that conducts sleep interviews to encourage the aging population to report behaviors that may affect their sleep, followed by providing personalized recommendations for better sleep based on participants' self-reported behaviors; (2) assess the self-reported sleep assessment changes before, during, and after using our automated sleep disturbance intervention chatbot; (3) assess the changes in objective sleep assessment recorded by a sleep tracking device before, during, and after using the automated chatbot MotivSleep.Methods: We will recruit 30 older adult participants from West London for this pilot study. Each participant will have a sleep analyzer installed under their mattress. This contactless sleep monitoring device passively records movements, heart rate, and breathing rate while participants are in bed. In addition, each participant will use our proposed chatbot MotivSleep, accessible on WhatsApp, to describe their sleep and behaviors related to their sleep and receive personalized recommendations for better sleep tailored to their specific reasons for disrupted sleep. We will analyze questionnaire responses before and after the study to assess their perception of our proposed chatbot; questionnaire responses before, during, and after the study to assess their subjective sleep quality changes; and sleep parameters recorded by the sleep analyzer throughout the study to assess their objective sleep quality changes.Results: Recruitment will begin in May 2023 through UK Dementia Research Institute Care Research and Technology Centre organized community outreach. Data collection will run from May 2023 until December 2023. We hypothesize that participants will perceive our proposed chatbot as intelligent and trustworthy; we also hypothesize that our proposed chatbot can help improve participants' subjective and objective sleep assessment throughout the study.Conclusions: The MotivSleep automated chatbot has the potential to provide additional care to older adults who wish to improve their sleep in more accessible and less costly ways than conventional face-to-face therapy.

To compare the 24-hour sleep assessment capabilities of two contactless sleep technologies (CSTs) to actigraphy in community-dwelling older adults. We collected 7 to 14 days of data at home from 35 older adults (age: 65-83), some with medical conditions, using Withings Sleep Analyser (WSA, n=29), Emfit-QS (Emfit, n=17), a standard actigraphy device (Actiwatch Spectrum [AWS, n=34]) and a sleep diary. We compared nocturnal and daytime sleep measures estimated by the CSTs and actigraphy without sleep diary information (AWS-A) against sleep diary assisted actigraphy (AWS|SD). Compared to sleep diary, both CSTs accurately determined the timing of nocturnal sleep (ICC: going to bed, getting out of bed, time in bed > 0.75) whereas the accuracy of AWS-A was much lower. Compared to AWS|SD, the CSTs overestimated nocturnal total sleep time (WSA: +92.71±81.16 min; Emfit: +101.47±75.95 min) as did AWS-A (+46.95±67.26 min). The CSTs overestimated sleep efficiency (WSA: +9.19±14.26 %; Emfit: +9.41±11.05 %) whereas AWS-A estimate (-2.38±10.06 %) was accurate. About 65% (n=23) of participants reported daytime naps either in-bed or elsewhere. About 90% in-bed nap periods were accurately determined by WSA while Emfit was less accurate. All three devices estimated 24-h sleep duration with an error of ≈10% compared to the sleep diary. CSTs accurately capture the timing of in-bed nocturnal sleep periods without the need for sleep diary information. However, improvements are needed in assessing parameters such as total sleep time, sleep efficiency and naps before these CSTs can be fully utilized in field settings.

Sleep has been suggested to contribute to myelinogenesis and associated structural changes in the brain. As a principal hallmark of sleep, slow-wave activity (SWA) is homeostatically regulated but also differs between individuals. Besides its homeostatic function, SWA topography is suggested to reflect processes of brain maturation. Here, we assessed whether interindividual differences in sleep SWA and its homeostatic response to sleep manipulations are associated with in-vivo myelin estimates in a sample of healthy young men. Two hundred twenty-six participants (18-31 y.) underwent an in-lab protocol in which SWA was assessed at baseline (BAS), after sleep deprivation (high homeostatic sleep pressure, HSP) and sleep saturation (low homeostatic sleep pressure, LSP). Early-night frontal SWA, its frontal to occipital predominance as well as the overnight exponential SWA decay were computed over sleep conditions. Semi-quantitative magnetization transfer saturation maps (MTsat), providing markers for myelin content, were acquired during a separate laboratory visit. Early-night frontal SWA was negatively associated with regionally decreased myelin estimates in the temporal portion of the inferior longitudinal fasciculus. By contrast, neither the responsiveness of SWA to sleep saturation or deprivation, its overnight dynamics, nor the frontal/occipital SWA ratiowere associated with brain structural indices. Our results indicate that frontal SWA generation tracks interindividual differences in continued structural brain re-organization during early adulthood. This stage of life is not only characterized by ongoing region-specific changes in myelin content, but also by a sharp decrease and a shift towards frontal predominance in SWA generation.

Laboratory-based sleep manipulations show asymmetries between positive and negative affect, but say little about how more specific moods might change, and over what time course.. We report extensive analyses of items from the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) during days following nights of chronic sleep restriction (6 hr sleep opportunity), during 40hr of acute sleep deprivation under constant routine conditions, and during a week-long forced desynchrony protocol in which participants lived on a 28-h day. Living in the laboratory resulted in medium effects sizes on all measures of positive affect (Attentiveness, General Positive Affect, Joviality, Assuredness), with a general deterioration as the day wore on. These effects were not found with negative moods. Sleep restriction reduced some positive affect, particularly Attentiveness (also General Positive), and increased Hostility. These effects were not found with negative affect. A burden of chronic sleep loss also led to lower positive affect when participants confronted the acute sleep loss challenge, and all positive affect, as well as Fearfulness, General Negative Affect and Hostility were affected. Sleeping at atypical circadian phases resulted mood change: all positive affect reduced, Hostility and General Negative Affect increased. Deteriorations increased the further participants slept from their typical nocturnal sleep. In most cases the changes induced by chronic or acute sleep loss or mis-time sleep waxed or waned across the waking day, with linear or various non-linear trends best fitting these time-awake-based changes. While extended laboratory stays do not emulate the fluctuating emotional demands of everyday living, these findings demonstrate that even in controlled settings mood changes systematically as sleep is shortened or mis-timed.

INTRODUCTION: Sleep disturbances are prevalent in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but it is currently not known whether night-to-night variation in sleep predicts day-to-day variation in vigilance, cognition, mood, and behavior (daytime measures). METHODS: Subjective and objective sleep and daytime measures were collected daily for two weeks in 15 participants with mild AD, 8 mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and 22 with no cognitive impairment (NCI). Associations between daytime measures and four principal components of sleep (duration, quality, continuity and latency) were quantified using mixed-model regression. RESULTS: Sleepiness, alertness, contentedness, everyday memory errors, serial subtraction and behavioral problems were predicted by at least one of the components of sleep, and in particular sleep duration and continuity. Associations between variation in sleep and daytime measures were linear or quadratic and often different in AD from NCI. DISCUSSION: These findings imply that daytime functioning in AD may be improved by interventions that target sleep continuity.

Introduction Longitudinal monitoring of vital signs provides a method for identifying changes to general health in an individual and particularly so in older adults. The nocturnal sleep period provides a convenient opportunity to assess vital signs. Contactless technologies that can be embedded into the bedroom environment are unintrusive and burdenless and have the potential to enable seamless monitoring of vital signs. To realise this potential, these technologies need to be evaluated against gold standard measures and in relevant populations. Methods We evaluated the accuracy of heart rate and breathing rate measurements of three contactless technologies (two under-mattress trackers: Withings sleep analyser (WSA) and Emfit QS (Emfit) and a bedside radar: Somnofy) in a sleep laboratory environment and assessed their potential to capture vital signs (heart rate and breathing rate) in a real-world setting. Data were collected in 35 community dwelling older adults aged between 65 and 83 years (mean ± SD: 70.8 ± 4.9; 21 men) during a one-night clinical polysomnography (PSG) in a sleep laboratory, preceded by 7 to 14 days of data collection at-home. Several of the participants had health conditions including type-2 diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and arthritis and ≈49% (n = 17) had moderate to severe sleep apnea while ≈29% (n = 10) had periodic leg movement disorder. The under-mattress trackers provided estimates of both heart rate and breathing rate while the bedside radar provided only breathing rate. The accuracy of the heart rate and breathing rate estimated by the devices was compared to PSG electrocardiogram (ECG) derived heart rate (beats per minute, bpm) and respiratory inductance plethysmography thorax (RIP thorax) derived breathing rate (cycles per minute, cpm). We also evaluated breathing disturbance indices of snoring and the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) available from the WSA. Results All three contactless technologies provided acceptable accuracy in estimating heart rate [mean absolute error (MAE) < 2.2 bpm and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) < 5%] and breathing rate (MAE ≤ 1.6 cpm and MAPE < 12%) at 1 minute resolution. All three contactless technologies were able to capture changes in heart rate and breathing rate across the sleep period. The WSA snoring and breathing disturbance estimates were also accurate compared to PSG estimates (R-squared: WSA Snore: 0.76, p < 0.001; WSA AHI: 0.59, p < 0.001). Conclusion Contactless technologies offer an unintrusive alternative to conventional wearable technologies for reliable monitoring of heart rate, breathing rate, and sleep apnea in community dwelling older adults at scale. They enable assessment of night-to-night variation in these vital signs, which may allow the identification of acute changes in health, and longitudinal monitoring which may provide insight into health trajectories.

Evidence suggests that anthropogenic climate change is accelerating and is affecting human health globally. Despite urgent calls to address health effects in the context of the additional challenges of environmental degradation, biodiversity loss and ageing populations, the effects of climate change on specific health conditions are still poorly understood. Neurological diseases contribute substantially to the global burden of disease, and the possible direct and indirect consequences of climate change for people with these conditions are a cause for concern. Unaccustomed temperature extremes can impair the brain’s systems of resilience, thereby exacerbating or increasing susceptibility to neurological disease. In this Perspective, we explore how changing weather patterns resulting from climate change affect sleep — an essential restorative human brain activity, the quality of which is important for people with neurological diseases. We also consider the pervasive and complex influences of climate change on two common neurological conditions: stroke and epilepsy. We highlight the urgent need for research into the mechanisms underlying the effects of climate change on the brain in health and disease. We also discuss how neurologists can respond constructively to the climate crisis by raising awareness and promoting mitigation measures and research, actions which will bring widespread co-benefits.

Biological rhythms pervade physiology and pathophysiology across multiple timescales. Because of the limited sensing and algorithm capabilities of neuromodulation device technology to-date, insight into the influence of these rhythms on the efficacy of bioelectronic medicine has been infeasible. As the development of new devices begins to mitigate previous technology limitations, we propose that future devices should integrate chronobiological considerations in their control structures to maximize the benefits of neuromodulation therapy. We motivate this proposition with preliminary longitudinal data recorded from patients with Parkinson's disease and epilepsy during deep brain stimulation therapy, where periodic symptom biomarkers are synchronized to sub-daily, daily, and longer timescale rhythms. We suggest a physiological control structure for future bioelectronic devices that incorporates time-based adaptation of stimulation control, locked to patient-specific biological rhythms, as an adjunct to classical control methods and illustrate the concept with initial results from three of our recent case studies using chronotherapy-enabled prototypes. [Display omitted] Biological sciences; Neuroscience; Biotechnology; Bioelectronics

Sleep and circadian rhythm dysfunction is prevalent in schizophrenia, is associated with distress and poorer clinical status, yet remains an under-recognized therapeutic target. The development of new therapies requires the identification of the primary drivers of these abnormalities. Understanding of the regulation of sleep–wake timing is now sufficiently advanced for mathematical model-based analyses to identify the relative contribution of endogenous circadian processes, behavioral or environmental influences on sleep-wake disturbance and guide the development of personalized treatments. Here, we have elucidated factors underlying disturbed sleep-wake timing by applying a predictive mathematical model for the interaction of light and the circadian and homeostatic regulation of sleep to actigraphy, light, and melatonin profiles from 20 schizophrenia patients and 21 age-matched healthy unemployed controls, and designed interventions which restored sleep-circadian function. Compared to controls, those with schizophrenia slept longer, had more variable sleep timing, and received significantly fewer hours of bright light (light > 500 lux), which was associated with greater variance in sleep timing. Combining the model with the objective data revealed that non 24-h sleep could be best explained by reduced light exposure rather than differences in intrinsic circadian period. Modeling implied that late sleep offset and non 24-h sleep timing in schizophrenia can be normalized by changes in environmental light–dark profiles, without imposing major lifestyle changes. Aberrant timing and intensity of light exposure patterns are likely causal factors in sleep timing disturbances in schizophrenia. Implementing our new model-data framework in clinical practice could deliver personalized and acceptable light–dark interventions that normalize sleep-wake timing.

Several cellular pathways contribute to neurodegenerative tauopathy-related disorders. Microglial activation, a major component of neuroinflammation, is an early pathological hallmark that correlates with cognitive decline, while the unfolded protein response (UPR) contributes to synaptic pathology. Sleep disturbances are prevalent in tauopathies and may also contribute to disease progression. Few studies have investigated whether manipulations of sleep influence cellular pathological and behavioural features of tauopathy. We investigated whether trazodone, a licensed antidepressant with hypnotic efficacy in dementia, can reduce disease-related cellular pathways and improve memory and sleep in male rTg4510 mice with a tauopathy-like phenotype. In a 9-week dosing regimen, trazodone decreased microglial NLRP3 inflammasome expression and phosphorylated p38mitogen-activated protein kinase levels which correlated with the NLRP3 inflammasome, the UPR effector ATF4, and total tau levels. Trazodone reduced theta oscillations during REM sleep and enhanced rapid eye movement (REM) sleep duration. Olfactory memory transiently improved, and memory performance correlated with REM sleep duration and theta oscillations. These findings on the effects of trazodone on the NLRP3 inflammasome, the unfolded protein response and behavioural hallmarks of dementia warrant further studies on the therapeutic value of sleep-modulating compounds for tauopathies.

Analyses of gene-expression dynamics in research on circadian rhythms and sleep homeostasis often describe these two processes using separate models. Rhythmically expressed genes are, however, likely to be influenced by both processes. We implemented a driven, damped harmonic oscillator model to estimate the contribution of circadian- and sleep-wake-driven influences on gene expression. The model reliably captured a wide range of dynamics in cortex, liver, and blood transcriptomes taken from mice and humans under various experimental conditions. Sleep-wake-driven factors outweighed circadian factors in driving gene expression in the cortex, whereas the opposite was observed in the liver and blood. Because of tissueand gene-specific responses, sleep deprivation led to a long-lasting intra- and inter-tissue desynchronization. The model showed that recovery sleep contributed to these long-lasting changes. The results demonstrate that the analyses of the daily rhythms in gene expression must take the complex interactions between circadian and sleep-wake influences into account. A record of this paper's transparent peer review process is included in the supplemental information.

BACKGROUND: Twenty-four-hour rhythmicity in mammalian tissues and organs is driven by local circadian oscillators, systemic factors, the central circadian pacemaker, and light-dark cycles. At the physiological level, the neural and endocrine systems synchronize gene expression in peripheral tissues and organs to the twenty-four-hour day cycle, and disruption of such regulation has been shown to lead to pathological conditions. Thus, monitoring rhythmicity in tissues/organs holds promise for circadian medicine, however most tissues and organs are not easily accessible in humans and alternative approaches to quantify circadian rhythmicity are needed. We investigated the overlap between rhythmic transcripts in human blood and transcripts shown to be rhythmic in 64 tissues/organs of the baboon, how these rhythms are aligned with light-dark cycles and each other, and whether timing of tissue-specific rhythmicity can be predicted from a blood sample. RESULTS: We compared rhythmicity in transcriptomic time series collected from humans and baboons using set logic, circular cross-correlation, circular clustering, functional enrichment analyses and least squares regression. Of the 759 orthologous genes that were rhythmic in human blood, 652 (86%) were also rhythmic in at least one baboon tissue and most of these genes were associated with basic processes such as transcription and protein homeostasis. 109 (17%) of the 652 overlapping rhythmic genes were reported as rhythmic in only one baboon tissue or organ and several of these genes have tissue/organ-specific functions. The timing of human and baboon rhythmic transcripts displayed prominent ‘night’ and ‘day’ clusters, with genes in the dark cluster associated with translation. Alignment between baboon rhythmic transcriptomes and the overlapping human blood transcriptome was significantly closer when light onset, rather than midpoint of light, or end of light period, was used as phase reference point. The timing of overlapping human and baboon rhythmic transcriptomes was significantly correlated in 25 tissue/organs with an average earlier timing of 3.21 h (SD 2.47 h) in human blood. CONCLUSIONS: The human blood transcriptome contains sets of rhythmic genes that overlap with rhythmic genes of tissues/organs in baboon. The rhythmic sets vary across tissues/organs, but the timing of most rhythmic genes is similar in human blood and baboon tissues/organs. These results have implications for development of blood transcriptome-based biomarkers for circadian rhythmicity in tissues and organs.

Study Objectives. Sleep disturbances and genetic variants have been identified as risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Our goal was to assess whether genome-wide polygenic risk scores (PRS) for AD associate with sleep phenotypes in young adults, decades before typical AD symptom onset. Methods. We computed whole-genome Polygenic Risk Scores (PRS) for AD and extensively phenotyped sleep under different sleep conditions, including baseline sleep, recovery sleep following sleep deprivation and extended sleep opportunity, in a carefully selected homogenous sample of healthy 363 young men (22.1 y ± 2.7) devoid of sleep and cognitive disorders. Results. AD PRS was associated with more slow wave energy, i.e. the cumulated power in the 0.5-4 Hz EEG band, a marker of sleep need, during habitual sleep and following sleep loss, and potentially with large slow wave sleep rebound following sleep deprivation. Furthermore, higher AD PRS was correlated with higher habitual daytime sleepiness. Conclusions. These results imply that sleep features may be associated with AD liability in young adults, when current AD biomarkers are typically negative, and the notion that quantifying sleep alterations may be useful in assessing the risk for developing AD.

Cortisol is a robust circadian signal that synchronises peripheral circadian clocks with the central clock in the suprachiasmatic nucleus via glucocorticoid receptors that regulate peripheral gene expression. Misalignment of the cortisol rhythm with the sleep–wake cycle, as occurs in shift work, is associated with negative health outcomes, but underlying molecular mechanisms remain largely unknown. We experimentally induced misalignment between the sleep–wake cycle and melatonin and cortisol rhythms in humans and measured time series blood transcriptomics while participants slept in-phase and out-of-phase with the central clock. The cortisol rhythm remained unchanged, but many glucocorticoid signalling transcripts were disrupted by mistimed sleep. To investigate which factors drive this dissociation between cortisol and its signalling pathways, we conducted bioinformatic and temporal coherence analyses. We found that glucocorticoid signalling transcripts affected by mistimed sleep were enriched for binding sites for the transcription factor SP1. Furthermore, changes in the timing of the rhythms of SP1 transcripts, a major regulator of transcription, and changes in the timing of rhythms in transcripts of the glucocorticoid signalling pathways were closely associated. Associations between the rhythmic changes in factors that affect SP1 expression and its activity, such as STAT3, EP300, HSP90AA1, and MAPK1, were also observed. We conclude that plasma cortisol rhythms incompletely reflect the impact of mistimed sleep on glucocorticoid signalling pathways and that sleep–wake driven changes in SP1 may mediate disruption of these pathways. These results aid understanding of mechanisms by which mistimed sleep affects health.

Sleep disturbances and genetic variants have been identified as risk factors for Alzheimer's disease (AD). Our goal was to assess whether genome-wide polygenic risk scores (PRS) for AD associate with sleep phenotypes in young adults, decades before typical AD symptom onset. We computed whole-genome PRS for AD and extensively phenotyped sleep under different sleep conditions, including baseline sleep, recovery sleep following sleep deprivation, and extended sleep opportunity, in a carefully selected homogenous sample of 363 healthy young men (22.1 years ± 2.7) devoid of sleep and cognitive disorders. AD PRS was associated with more slow-wave energy, that is, the cumulated power in the 0.5-4 Hz EEG band, a marker of sleep need, during habitual sleep and following sleep loss, and potentially with larger slow-wave sleep rebound following sleep deprivation. Furthermore, higher AD PRS was correlated with higher habitual daytime sleepiness. These results imply that sleep features may be associated with AD liability in young adults, when current AD biomarkers are typically negative, and support the notion that quantifying sleep alterations may be useful in assessing the risk for developing AD.

Twenty-four-hour rhythms in physiology and behaviour are shaped by circadian clocks, environmental rhythms, and feedback of behavioural rhythms onto physiology. In space, 24 h signals such as those associated with the light-dark cycle and changes in posture, are weaker, potentially reducing the robustness of rhythms. Head down tilt (HDT) bed rest is commonly used to simulate effects of microgravity but how HDT affects rhythms in physiology has not been extensively investigated. Here we report effects of -6 degrees HDT during a 90-day protocol on 24 h rhythmicity in 20 men. During HDT, amplitude of light, motor activity, and wrist-temperature rhythms were reduced, evening melatonin was elevated, while cortisol was not affected during HDT, but was higher in the morning during recovery when compared to last session of HDT. During recovery from HDT, time in Slow-Wave Sleep increased. EEG activity in alpha and beta frequencies increased during NREM and REM sleep. These results highlight the profound effects of head-down-tilt-bed-rest on 24 h rhythmicity.

Accurate assessment of the intrinsic period of the human circadian pacemaker is essential for a quantitative understanding of how our circadian rhythms are synchronized to exposure to natural and man-made light-dark (LD) cycles. The gold standard method for assessing intrinsic period in humans is forced desynchrony (FD) which assumes that the confounding effect of lights-on assessment of intrinsic period is removed by scheduling sleep-wake and associated dim LD cycles to periods outside the range of entrainment of the circadian pacemaker. However, the observation that the mean period of free-running blind people is longer than the mean period of sighted people assessed by FD (24.50 0.17 h vs 24.15 0.20 h, 0.001) appears inconsistent with this assertion. Here, we present a mathematical analysis using a simple parametric model of the circadian pacemaker with a sinusoidal velocity response curve (VRC) describing the effect of light on the speed of the oscillator. The analysis shows that the shorter period in FD may be explained by exquisite sensitivity of the human circadian pacemaker to low light intensities and a VRC with a larger advance region than delay region. The main implication of this analysis, which generates new and testable predictions, is that current quantitative models for predicting how light exposure affects entrainment of the human circadian system may not accurately capture the effect of dim light. The mathematical analysis generates new predictions which can be tested in laboratory experiments. These findings have implications for managing healthy entrainment of human circadian clocks in societies with abundant access to light sources with powerful biological effects.

Alpha oscillations play a vital role in managing the brain's resources, inhibiting neural activity as a function of their phase and amplitude, and are changed in many brain disorders. Developing minimally invasive tools to modulate alpha activity and identifying the parameters that determine its response to exogenous modulators is essential for the implementation of focussed interventions. We introduce Alpha Closed-Loop Auditory Stimulation (αCLAS) as an EEG-based method to modulate and investigate these brain rhythms in humans with specificity and selectivity, using targeted auditory stimulation. Across a series of independent experiments, we demonstrate that αCLAS alters alpha power, frequency, and connectivity in a phase, amplitude, and topography-dependent manner. Using single-pulse-αCLAS, we show that the effects of auditory stimuli on alpha oscillations can be explained within the theoretical framework of oscillator theory and a phase-reset mechanism. Finally, we demonstrate the functional relevance of our approach by showing that αCLAS can interfere with sleep onset dynamics in a phase-dependent manner.

Data sources and code used for the analyses are found in the file called PLSR_16.zip which contains the following files and folders: File_contents_description.txt (detailed description of the files included in the zip file), TRAINING_SAMPLES_MicroarrayInformation.csv (description of the microarray samples conforming the training set), Training_Processed_SingleDataset.csv (pre-processed, normalised and filtered (i.e. ready to use) microarray data matrix conforming the training set), Training_TwoSamples_SamplingTable.csv (table describing the pairing of samples 12 hrs apart within the training set), VALIDATION_SAMPLES_MicroarrayInformation.csv (description of the microarray samples conforming the validation set), Validation_Processed_SingleDataset.csv (pre-processed, normalised and filtered (i.e. ready to use) microarray data matrix conforming the validation set), Validation_TwoSamples_SamplingTable.csv (table describing the pairing of samples 12 hrs apart within the validation set), Code (folder with R scripts (.R) described in Code/RUNNING_CODE_README.txt file). Further information about the methodology used can be found in the journal paper https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.20214.

Training and validation processed datasets used in the analyses can be found in the file called SleepDebt.zip which contains the following folders: TimeAwake, SleepIncreaseDecrease, ChronicSleepInsufficiency and AcuteSleepLoss. Each folder contains R object files [.RData] with training and validation datasets, prediction labels and R2 in each set and lambda used in the regression analyses. Instrument- or software-specific information needed to interpret the data: R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/. Further information about the methodology used can be found in the journal paper (Sleep, Volume 42, Issue 1, January 2019, zsy186).

Sleep disturbances have been reported as one of the most common symptoms among people living with dementia (PLWD). Few technologies to longitudinally monitor sleep across the 24-h day are available. Here, we develop machine learning models that use multimodal data to accurately monitor sleep across the day and night.

The daily alternation between sleep and wakefulness is one of the most dominant features of our lives and is a manifestation of the intrinsic 24 h rhythmicity underlying almost every aspect of our physiology. Circadian rhythms are generated by networks of molecular oscillators in the brain and peripheral tissues that interact with environmental and behavioural cycles to promote the occurrence of sleep during the environmental night. This alignment is often disturbed, however, by contemporary changes to our living environments, work or social schedules, patterns of light exposure, and biological factors, with consequences not only for sleep timing but also for our physical and mental health. Characterised by undesirable or irregular timing of sleep and wakefulness, in this Series paper we critically examine the existing categories of circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders and the role of the circadian system in their development. We emphasise how not all disruption to daily rhythms is driven solely by an underlying circadian disturbance, and take a broader, dimensional approach to explore how circadian rhythms and sleep homoeostasis interact with behavioural and environmental factors. Very few high-quality epidemiological and intervention studies exist, and wider recognition and treatment of sleep timing disorders are currently hindered by a scarcity of accessible and objective tools for quantifying sleep and circadian physiology and environmental variables. We therefore assess emerging wearable technology, transcriptomics, and mathematical modelling approaches that promise to accelerate the integration of our knowledge in sleep and circadian science into improved human health.

Introduction Sleep plays a crucial role in brain plasticity, and has been suggested to be involved in myelin organization. Here we assessed the association between sleep homeostatic responses and quantitative MRI-derived myelin content in a sample of healthy young men. Methods: 238 male participants (age: 22.12.7) underwent an in-lab protocol to assess homeostatic responses in slow wave and REM sleep through a modulation of prior wakefulness and sleep duration. The protocol encompassed four conditions: a baseline night (BAS, duration adjusted on participant’s sleep-wake schedule), a 12h sleep extension night (EXT) followed by a 4-h nap and an 8-h sleep opportunity night (sleep saturation; SAT) and a 12h recovery night (REC) following 40-hours sleep deprivation. For each night, four sleep parameters were extracted: sleep slow wave activity at the beginning of the night (SWA0), its overnight exponential dissipation rate (tau), and overnight mean theta and beta power per REM epoch. Participants underwent a multiparameter brain MRI protocol at 3T to extract quantitative maps sensitive to different myelin biomarkers. F-contrasts were calculated to assess whether the modularity of sleep parameters across sleep conditions explains variance in myelin biomarkers. Reported statistics are family-wise-error corrected over the entire brain volume (pFWE BAS>EXT>SAT; all p < 0.001), while REM sleep percentage significantly differed only between SAT and the other sleep contexts (F(3,1257)= 13.676743, p

Sleep timing varies between individuals and can be altered in mental and physical health conditions. Sleep and circadian sleep phenotypes, including circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders, may be driven by endogenous physiological processes, exogeneous environmental light exposure, social constraints or behavioural factors. Identifying the relative contributions of these driving factors to different phenotypes is essential for the design of personalised sleep interventions. The timing of the human sleep-wake cycle has been modelled as an interaction between a relaxation oscillator (the sleep homeostat), a stable limit cycle oscillator with a near 24-hour period (the circadian process), man-made light exposure, and the natural light-dark cycle generated by the Earth's rotation. However, these models have rarely been used to quantitatively describe sleep at the individual level. Here, we present a new Homeostatic-Circadian-Light model (HCL) which is simpler, more transparent, and more computationally efficient than other available models and is designed to run using longitudinal sleep and light exposure data from wearable sensors. We carry out a systematic sensitivity analysis for all model parameters and discuss parameter identifiability. We demonstrate we can describe individual sleep phenotypes in each of 34 older participants (65-83y) by feeding individual participant light exposure patterns into the model and fitting two parameters that capture individual average sleep duration and timing. The fitted parameters describe endogenous drivers of sleep phenotypes. We then quantify exogenous drivers using a novel metric which encodes the circadian phase dependence of the response to light. Combining endogenous and exogeneous drivers better explains individual mean mid-sleep (adjusted R-squared 0.64) than either driver on its own (adjusted R-squared 0.08 and 0.17 respectively). Critically, our model and analysis highlights different people exhibiting the same sleep phenotype may have different driving factors and opens the door to personalised interventions to regularize sleep-wake timing that are readily implementable with current digital health technology.Competing Interest StatementDJD and ACS are consultants to F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Ltd.Footnotes* This version of the manuscript has been revised to: - take account of referees comments - updated to correct minor errors, including typographical errors. The central messages and mathematical modelling remain unchanged.* https://github.com/anneskeldon/Homeostatic_circadian_light_model-factors_driving_sleep_phenotypes

Plasma biomarkers of dementia, including phosphorylated tau (p-tau217), offer promise as tools for diagnosis, stratification for clinical trials, monitoring disease progression, and assessing the success of interventions in those living with Alzheimer's disease. However, currently, it is unknown whether these dementia biomarker levels vary with the time of day, which could have implications for their clinical value. In two protocols, we studied 38 participants (70.8 ± 7.6 years; mean ± SD) in a 27-h laboratory protocol with either two samples taken 12 h apart or 3-hourly blood sampling for 24 h in the presence of a sleep-wake cycle. The study population comprised people living with mild Alzheimer's disease (PLWA, n = 8), partners/caregivers of PLWA (n = 6) and cognitively intact older adults (n = 24). Single-molecule array technology was used to measure phosphorylated tau (p-tau217) (ALZpath), amyloid-beta 40 (Aβ40), amyloid-beta 42 (Aβ42), glial fibrillary acidic protein, and neurofilament light (NfL) (Neuro 4-Plex E). Analysis with a linear mixed model (SAS, PROC MIXED) revealed a significant effect of time of day for p-tau217, Aβ40, Aβ42, and NfL, and a significant effect of participant group for p-tau217. For p-tau217, the lowest levels were observed in the morning upon waking and the highest values in the afternoon/early evening. The magnitude of the diurnal variation for p-tau217 was similar to the reported increase in p-tau217 over one year in amyloid-β-positive mild cognitively impaired people. Currently, the factors driving this diurnal variation are unknown and could be related to sleep, circadian mechanisms, activity, posture, or meals. Overall, this work implies that the time of day of sample collection may be relevant in the implementation and interpretation of plasma biomarkers in dementia research and care.

Abstract Background Increased daytime napping and excessive sleepiness are associated with cognitive decline in older adults, especially in people living with dementia (PLWD) [1]. Subjective assessments of naps are burdensome and maybe unreliable in PLWD and hence there is a need for technologies that provide objective longitudinal assessment of the incidence and duration of naps. Here we compare two contactless sleep technologies (CSTs) against sleep diary and actigraphy for monitoring daytime napping in community dwelling non‐demented older adults. Method Two under‐mattress CSTs (Withings Sleep Analyser [WSA] and Emfit QS [Emfit]) along with actigraphy (Actiwatch Spectrum [AWS]) were deployed in the home of 17 older adults for a period of 14 days ( = 65 years; Mean Age ± SD = 72 ± 4.49; 6 Women). The ground truth nap information was collected using an extended consensus sleep diary that included additional information about naps (timing, duration, and location). We analyzed the agreement of the napping events and duration estimated by WSA, Emfit and AWS against the sleep diary reported events. Result The CSTs only detected in‐bed naps whilst the AWS detected both in‐bed and not‐in‐bed naps. Although all the compared devices detected spurious naps unreported in the sleep diary, it was highest in AWS (81% of total naps detected) followed by Emfit (63%) and WSA (16%) as shown in Figure 1. Among the CSTs, WSA accurately detected more in bed naps while registering less spurious naps compared to Emfit but had lower duration agreement to sleep diary (Figure 2). Further, when the contribution of daytime naps to 24‐h total sleep time was computed, the WSA estimate (12.8±6.1%) was closest to the sleep diary estimate (12.9±9.1%) followed by AWS (15.6±9.9%) and Emfit (17.2±11.1%). Conclusion CSTs, with their ability to provide both contextual location information and objective measures of napping, such as timing and duration, offer a reliable and unobtrusive alternative to traditional methods such as sleep diary and actigraphy for long‐term round‐the‐clock monitoring of sleep in older adults. References: [1] Li, P, Gao, L, Yu, L, et al. Daytime napping, and Alzheimer’s dementia: A potential bidirectional relationship. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023; 19: 158– 168. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.12636

Period3 (Per3) is one of the most robustly rhythmic genes in humans and animals. It plays a significant role in temporal organisation in peripheral tissues. The effects of PER3 variants on many phenotypes have been investigated in targeted and genome-wide studies. PER3 variants, especially the human variable number tandem repeat (VNTR), associate with diurnal preference, mental disorders, non-visual responses to light, brain and cognitive responses to sleep loss/circadian misalignment. Introducing the VNTR into mice alters responses to sleep loss and expression of sleep homeostasis-related genes. Several studies were limited in size and some findings were not replicated. Nevertheless, the data indicate a significant contribution of PER3 to sleep and circadian phenotypes and diseases, which may be connected by common pathways. Thus, PER3-dependent altered light sensitivity could relate to high retinal PER3 expression and may contribute to altered brain response to light, diurnal preference and seasonal mood. Altered cognitive responses during sleep loss/circadian misalignment and changes to slow wave sleep may relate to changes in wake/activity-dependent patterns of hypothalamic gene expression involved in sleep homeostasis and neural network plasticity. Comprehensive characterisation of effects of clock gene variants may provide new insights into the role of circadian processes in health and disease.

Vigilance states, electroencephalogram (EEG) power spectra (0.25-25.0 Hz), and cortical temperature (TCRT) of 10 rats were obtained during a baseline day, a 24-h sleep deprivation (SD) period, and 2 days of recovery (recoveries 1 and 2). EEG power density in waking gradually increased in most frequencies during the SD period. Non-rapid-eye-movement (NREM) sleep was enhanced on both recovery days, and rapid-eye-movement sleep was enhanced only on recovery 1. In the initial 4 h of recovery 1, EEG slow-wave activity (SWA; mean power density 0.75-4.0 Hz) in NREM sleep was elevated relative to baseline, and the number of brief awakenings (nBA) was reduced. In the dark period of recovery 1 and the light period of recovery 2, SWA was below baseline, and nBA was increased. During the entire recovery period, SWA and nBA, both expressed as deviation from baseline values, were negatively correlated. During the SD period, TCRT was above baseline, and in the initial 16 h of recovery 1 it was below baseline. Whereas TCRT was negatively correlated with NREM sleep, no significant correlation was found between TCRT and SWA within NREM sleep. It is concluded that SD causes a short-lasting intensification of sleep, as indicated by the enhanced SWA and the reduced nBA, and a long-lasting increase in sleep duration. The different time courses of SWA and TCRT suggest that variations in NREM sleep intensity are not directly related to changes in TCRT.

In nine subjects sleep was recorded under base-line conditions with a habitual bedtime (prior wakefulness 16 h; lights off at 2300 h) and during recovery from sleep deprivation with a phase-advanced bedtime (prior wakefulness 36 h; lights off at 1900 h). The duration of phase-advanced recovery sleep was greater than 12 h in all subjects. Spectral analysis of the sleep electroencephalogram (EEG) revealed that slow-wave activity (SWA; 0.75-4.5 Hz) in non-rapid-eye-movement (NREM) sleep was significantly enhanced during the first two NREM-REM sleep cycles of displaced recovery sleep. The sleep stages 3 and 4 (slow-wave sleep) and SWA decreased monotonically over the first three and four NREM-REM cycles of, respectively, base-line and recovery sleep. The time course of SWA in base-line and recovery sleep could be adequately described by an exponentially declining function with a horizontal asymptote. The results are in accordance with the two-process model of sleep regulation in which it is assumed that SWA rises as a function of the duration of prior wakefulness and decreases exponentially as a function of prior sleep. We conclude that the present data do not provide evidence for a 12.5-h sleep-dependent rhythm of deep NREM sleep.

Objective: Sleep monitoring has extensively utilized electroencephalogram (EEG) data collected from the scalp, yielding very large data repositories and well-trained analysis models. Yet, this wealth of data is lacking for emerging, less intrusive modalities, such as ear-EEG.Methods and procedures: The current study seeks to harness the abundance of open-source scalp EEG datasets by applying models pre-trained on data, either directly or with minimal fine-tuning; this is achieved in the context of effective sleep analysis from ear-EEG data that was recorded using a single in-ear electrode, referenced to the ipsilateral mastoid, and developed in-house as described in our previous work. Unlike previous studies, our research uniquely focuses on an older cohort (17 subjects aged 65-83, mean age 71.8 years, some with health conditions), and employs LightGBM for transfer learning, diverging from previous deep learning approaches. Results: Results show that the initial accuracy of the pre-trained model on ear-EEG was 70.1%, but fine-tuning the model with ear-EEG data improved its classification accuracy to 73.7%. The fine-tuned model exhibited a statistically significant improvement (p < 0.05, dependent t-test) for 10 out of the 13 participants, as reflected by an enhanced average Cohen's kappa score (a statistical measure of inter-rater agreement for categorical items) of 0.639, indicating a stronger agreement between automated and expert classifications of sleep stages. Comparative SHAP value analysis revealed a shift in feature importance for the N3 sleep stage, underscoring the effectiveness of the fine-tuning process.Conclusion: Our findings underscore the potential of fine-tuning pre-trained scalp EEG models on ear-EEG data to enhance classification accuracy, particularly within an older population and using feature-based methods for transfer learning. This approach presents a promising avenue for ear-EEG analysis in sleep studies, offering new insights into the applicability of transfer learning across different populations and computational techniques.Clinical impact: An enhanced ear-EEG method could be pivotal in remote monitoring settings, allowing for continuous, non-invasive sleep quality assessment in elderly patients with conditions like dementia or sleep apnea.

This British Association for Psychopharmacology guideline replaces the original version published in 2010, and contains updated information and recommendations. A consensus meeting was held in London in October 2017 attended by recognised experts and advocates in the field. They were asked to provide a review of the literature and identification of the standard of evidence in their area, with an emphasis on meta-analyses, systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials where available, plus updates on current clinical practice. Each presentation was followed by discussion, aiming to reach consensus where the evidence and/or clinical experience was considered adequate, or otherwise to flag the area as a direction for future research. A draft of the proceedings was circulated to all speakers for comments, which were incorporated into the final statement.

•Sleep is a key concern in dementias but their sleep phenotypes are not well defined.•We addressed this issue in major FTD and AD syndromes versus healthy older controls.•We surveyed sleep duration, quality and disruptive events, and daytime somnolence.•Sleep symptoms were frequent in FTD and AD and distinguished these diseases.•Sleep disturbance is an important clinical issue across major FTD and AD syndromes. Sleep disruption is a key clinical issue in the dementias but the sleep phenotypes of these diseases remain poorly characterised. Here we addressed this issue in a proof-of-principle study of 67 patients representing major syndromes of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), in relation to 25 healthy older individuals. We collected reports on clinically-relevant sleep characteristics - time spent overnight in bed, sleep quality, excessive daytime somnolence and disruptive sleep events. Difficulty falling or staying asleep at night and excessive daytime somnolence were significantly more frequently reported for patients with both FTD and AD than healthy controls. On average, patients with FTD and AD retired earlier and patients with AD spent significantly longer in bed overnight than did healthy controls. Excessive daytime somnolence was significantly more frequent in the FTD group than the AD group; AD syndromic subgroups showed similar sleep symptom profiles while FTD subgroups showed more variable profiles. Sleep disturbance is a significant clinical issue in major FTD and AD variant syndromes and may be even more salient in FTD than AD. These preliminary findings warrant further systematic investigation with electrophysiological and neuroanatomical correlation in major proteinopathies.

Disturbances of the sleep-wake cycle are highly prevalent and diverse. The aetiology of some sleep disorders, such as circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders, is understood at the conceptual level of the circadian and homeostatic regulation of sleep and in part at a mechanistic level. Other disorders such as insomnia are more difficult to relate to sleep regulatory mechanisms or sleep physiology. To further our understanding of sleep-wake disorders and the potential of novel therapeutics, we discuss recent findings on the neurobiology of sleep regulation and circadian rhythmicity and its relation with the subjective experience of sleep and the quality of wakefulness. Sleep continuity and to some extent REM sleep emerge as determinants of subjective sleep quality and waking performance. The effects of insufficient sleep primarily concern subjective and objective sleepiness as well as vigilant attention, whereas performance on higher cognitive functions appears to be better preserved albeit at the cost of increased effort. We discuss age-related, sex and other trait-like differences in sleep physiology and sleep need and compare the effects of existing pharmacological and non-pharmacological sleep- and wake-promoting treatments. Successful non-pharmacological approaches such as sleep restriction for insomnia and light and melatonin treatment for circadian rhythm sleep disorders target processes such as sleep homeostasis or circadian rhythmicity. Most pharmacological treatments of sleep disorders target specific signalling pathways with no well-established role in either sleep homeostasis or circadian rhythmicity. Pharmacological sleep therapeutics induce changes in sleep structure and the sleep EEG which are specific to the mechanism of action of the drug. Sleep- and wake-promoting therapeutics often induce residual effects on waking performance and sleep, respectively. The need for novel therapeutic approaches continues not at least because of the societal demand to sleep and be awake out of synchrony with the natural light-dark cycle, the high prevalence of sleep-wake disturbances in mental health disorders and in neurodegeneration. Novel approaches, which will provide a more comprehensive description of sleep and allow for large-scale sleep and circadian physiology studies in the home environment, hold promise for continued improvement of therapeutics for disturbances of sleep, circadian rhythms and waking performance.

Sleep in mammals consists of non-rapid-eye-movement and rapid-eye movement sleep. A large genetic screen reveals that these two sleep states are altered in mice by mutations dubbed Sleepy and Dreamless. SEE ARTICLE p.378

SUMMARY Night work is associated with increased sleepiness and disturbed sleep. Maladaptation of the circadian system, which is phase‐adjusted to day time work and thus promotes sleepiness during its nadir at night and wakefulness (or disturbed sleep) during the day, contributes substantially to this problem. A major cause of suboptimal circadian phase adjustment among night workers is the exposure to morning light, which prevents the delay needed for optimal adjustment to night work. Several laboratory studies indicate that careful application of bright light may cause the circadian system to shift to any desired phase. Furthermore, studies of simulated night work demonstrate that night exposure to bright light can virtually eliminate circadian maladjustment among night workers. While the results are promising, there is still, however, an urgent need for longitudinal studies of bright light application in. real‐life settings.

Abstract Adrenal glucocorticoids are major modulators of multiple functions, including energy metabolism, stress responses, immunity, and cognition. The endogenous secretion of glucocorticoids is normally characterized by a prominent and robust circadian (around 24 hours) oscillation, with a daily peak around the time of the habitual sleep-wake transition and minimal levels in the evening and early part of the night. It has long been recognized that this 24-hour rhythm partly reflects the activity of a master circadian pacemaker located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus. In the past decade, secondary circadian clocks based on the same molecular machinery as the central master pacemaker were found in other brain areas as well as in most peripheral tissues, including the adrenal glands. Evidence is rapidly accumulating to indicate that misalignment between central and peripheral clocks has a host of adverse effects. The robust rhythm in circulating glucocorticoid levels has been recognized as a major internal synchronizer of the circadian system. The present review examines the scientific foundation of these novel advances and their implications for health and disease prevention and treatment.

Advances in diagnostic technology, including chronic intracranial EEG recordings, have confirmed the clinical observation of different temporal patterns of epileptic activity and seizure occurrence over a 24-h period. The rhythmic patterns in epileptic activity and seizure occurrence are probably related to vigilance states and circadian variation in excitatory and inhibitory balance. Core circadian genes BMAL1 and CLOCK, which code for transcription factors, have been shown to influence excitability and seizure threshold. Despite uncertainties about the relative contribution of vigilance states versus circadian rhythmicity, including circadian factors such as seizure timing improves sensitivity of seizure prediction algorithms in individual patients. Improved prediction of seizure occurrence opens the possibility for personalised antiepileptic drug-dosing regimens timed to particular phases of the circadian cycle to improve seizure control and to reduce side-effects and risks associated with seizures. Further studies are needed to clarify the pathways through which rhythmic patterns of epileptic activity are generated, because this might also inform future treatment options.

Sleep timing and sleep structure vary between and within individuals and are regulated by two main processes: sleep homeostasis and circadian rhythmicity. Homeostasis refers to the ability of an organism to maintain an internal biologic equilibrium through regulatory mechanisms. Homeostatic regulation of sleep has been demonstrated by driving the system away from a state of equilibrium through total, partial, and sleep stage specific deprivation and then monitoring the resultant changes in sleep. The homeostatic regulation of slow-wave activity has been quantified in detail but other aspects of sleep, such as sleep duration and REM sleep, are also under homeostatic control. All these aspects of sleep are also affected by circadian rhythmicity. The joint regulation of sleep timing by homeostasis and circadian rhythmicity has been formalised in the two-process model of sleep regulation. More recently, effects of light on the human circadian pacemaker have been incorporated in models of sleep regulation and other models developed to describe the ultradian NREM-REM cycle. Conceptual models of sleep regulation summarise accumulated knowledge and extract essential principles underlying empirical facts. Mathematical models can in addition test whether our understanding of phenomena as formulated in conceptual frameworks is sufficient to explain these phenomena quantitatively. Ultimately, models for sleep regulation should help us to understand sleep phenotypes, treat sleep disturbances, design physical and social environments to maximise the beneficial effects of sleep, and inform the development of policies to minimise the negative effects of insufficient and mistimed sleep.

Sleep is a process of rest and renewal that is vital for humans. However, there are several sleep disorders such as rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behaviour disorder (RBD), sleep apnea, and restless leg syndrome (RLS) that can have an impact on a significant portion of the population. These disorders are known to be associated with particular behaviours such as specific body positions and movements. Clinical diagnosis requires patients to undergo polysomnography (PSG) in a sleep unit as a gold standard assessment. This involves attaching multiple electrodes to the head and body. In this experiment, we seek to develop non-contact approach to measure sleep disorders related to body postures and movement. An Infrared (IR) camera is used to monitor body position unaided by other sensors. Twelve participants were asked to adopt and then move through a set of 12 pre-defined sleep positions. We then adopted convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for automatic feature generation from IR data for classifying different sleep postures. The results show that the proposed method has an accuracy of between 0.76 & 0.91 across the participants and 12 sleep poses with, and without a blanket cover, respectively. The results suggest that this approach is a promising method to detect common sleep postures and potentially characterise sleep disorder behaviours.

Introduction Disturbances of sleep/wake behaviour are amongst the most disabling symptoms of dementia, leading to increased carers’ burden and institutionalisation. The lack of unobtrusive, low- burden technologies validated to monitor sleep in patients living with dementia (PLWD) has prevented longitudinal studies of nocturnal disturbances and their correlates. Aims To examine the effect of medication changes and clinical status on the intraindividual variation in sleep/wake behaviour in PLWD. Methods Using under-mattress pressure-sensing mat in 46 PLWD, we monitored sleep/wake behavioural metrics for 13,711 nights between 2019-2021. Machine learning and >3.6million nightly summaries from 13,671 individuals from the general population were used to detect abnormalities in PLWD’s nightly sleep/wake metrics and convert them to risk scores. Additionally, GP records were reviewed for each patient to determine whether medication changes and clinical events affected sleep parameters. Results PLWD’s went to bed earlier and rose later than sex- and age-matched controls. They had more nocturnal awakenings with longer out-of-bed durations. Notably, at the individual patient level, increased metric-specific risk scores were temporally related to changes in antipsychotics and antidepressants, and acute illness, including UTI, cardiac events, and depressive episodes. Conclusions Passive monitoring of sleep/wake behaviours is a promising way to identify novel markers of disease progression and evaluate the effectiveness of pharmaceutical interventions in patients with dementia.

Timing of the human sleep-wake cycle is determined by social constraints, biological processes (sleep homeostasis and circadian rhythmicity) and environmental factors, particularly natural and electrical light exposure. To what extent seasonal changes in the light-dark cycle affect sleep timing and how this varies between weekdays and weekends has not been firmly established. We examined sleep and activity patterns during weekdays and weekends in late autumn (standard time, ST) and late spring (daylight saving time, DST), and expressed their timing in relation to three environmental reference points: clock-time, solar noon (SN), which occurs one clock hour later during DST than ST, and the midpoint of accumulated light exposure (50%-LE). Observed sleep timing data were compared to simulated data from a mathematical model for the effects of light on the circadian and homeostatic regulation of sleep. A total of 715 days of sleep timing and light exposure were recorded in 19 undergraduates in a repeated-measures observational study. During each three-week assessment, light and activity were monitored, and self-reported bed and wake times were collected. Light exposure was higher in spring than in autumn. 50%-LE did not vary across season, but occurred later on weekends compared to weekdays. Relative to clock-time, bedtime, wake-time, mid-sleep, and midpoint of activity were later on weekends but did not differ across seasons. Relative to SN, sleep and activity measures were earlier in spring than in autumn. Relative to 50%-LE, only wake-time and mid-sleep were later on weekends, with no seasonal differences. Individual differences in mid-sleep did not correlate with SN but correlated with 50%-LE. Individuals with different habitual bedtimes responded similarly to seasonal changes. Model simulations showed that light exposure patterns are sufficient to explain sleep timing in spring but less so in autumn. The findings indicate that during autumn and spring, the timing of sleep associates with actual light exposure rather than sun time as indexed by SN.